Everything consists of spacetime.

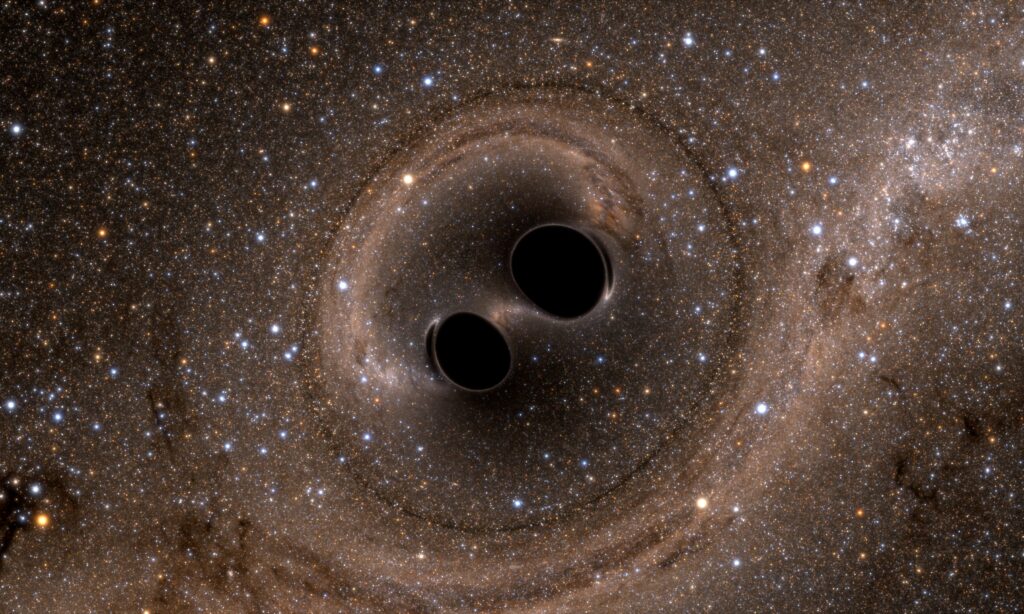

SR is based on only two principles

That sounds very simple. It is. Nevertheless, we will have to look at things here contrary to the textbook approach. With the DP, we have shifted an aspect that is important for the principle of relativity. It appears that spacetime density and thus also the state of motion has an “absolute” value. We will see that we cannot obtain absolute value in the SRT. However, there is information about smaller and larger between states of motion. According to the textbook approach to the principle of relativity, this is not allowed. Every object can be considered at rest, and there can be no smaller or larger. Even the term “state of motion” is incorrect here. This always depends on the chosen reference system. It is not possible to clearly assign a state of motion to an object. But that is exactly what we will do. To top it off, we will derive the principle of relativity for everything that exists in the universe. We cannot simply accept the principle of relativity as a postulate. We must justify it properly. Sounds exciting.

The counterargument always arises that the DP is a kind of Lorentz ether theory. It is important to note that we never use an ether. There is only spacetime. An additional ether in any form is explicitly prohibited by the DP. A fitting thought from the DP is that spacetime and ether are identical. Spacetime in the DP loses a crucial property compared to ether: spacetime can never serve as a reference for a rest point. But that is exactly what ether was built for. We must also take a closer look at this because the mathematics of the ether has been incorporated into Einstein’s principle of relativity.

We have already shown in the previous chapter that the speed of light exists as a maximum speed. However, that is not enough. The postulate of the speed of light has two properties. It must also be shown why this limit is identical for every observer locally. If there is a smaller and a larger, then we can determine who is closer to the spacetime limit, right? No, we cannot. This has nothing to do with the fact that the speed of light is defined identically for all observers. Once again, it is a matter of all deformations of spacetime being a local change in the definition of geometry.

Contrary to previous explanations, we must start from scratch here. We will take the classic approach. We will start with Galileo and move on to Newton, Maxwell, Lorentz, and Einstein. Then we will see that Einstein got everything right with his combination of the speed of light and the principle of relativity, but he also allowed himself a lot of fun. This is often overlooked, but it is essential for us. Therefore, we will take a closer look at the sequence of developments. I realize that this section may be a bit tedious for “insiders.” Please read it anyway. I am curious to see if you are already familiar with this insight. Most people overlook this and jump straight to the calculations. But then you haven’t discovered the fun part of SR.

Galileo is often regarded as the forefather of modern physics. For us, Galileo introduced one of the most important thought experiments in physics, the closed box. We need this in SR without interaction and in GR with interaction. This was the basic idea behind Galileo’s principle of relativity. For Galileo, the closed box was a ship’s cabin with no way of seeing outside. The whole thing was in very calm, flowing water. For Einstein, it was an elevator and later a spaceship. Everyone is a child of their time.

When we sit in a ship’s cabin, we cannot determine whether we are moving with the water or standing still. This is identical to the question: Are we flowing with the water, or is the water flowing under the ship? There is no frame of reference or reference point to clearly determine the movement. From this, it can be deduced that movement can generally only be determined relative to a reference point. We extend the thought experiment with two boxes that only have a small viewing slit open. Nothing else can be seen except the boxes themselves.

If we sit in one box and look out, we can see the other box passing by our box at a constant speed. If we cannot feel any acceleration, then we cannot determine whether we are moving and the other is at rest, or vice versa. Both boxes could be moving at different speeds, and neither is at rest. Both boxes could also be moving at the same speed in one direction, in which case we would not detect any movement between the boxes. The only detectable variable is the difference in movement between the two boxes. We can only determine the relative movement of the boxes in relation to each other. This results in the principle of relativity.

A principle of relativity always involves a transformation. This is the change of perspective from one box to the other. This is called the Galileo transformation. The calculation is so simple that a physics student would probably not be given exercise on it. This is precisely where the problem lies. Galileo’s principle of relativity is so simple that no one bothers to think through the fundamentals. It is explained briefly, and that’s it, done and dusted. We must make an effort to work out the basic principle behind it.

The crucial question is: When do we obtain a principle of relativity? Let’s address this fundamental question. The approach comes from the example of two boxes. A principle of relativity only arises if we can determine differences between objects (boxes) exclusively. We extend this statement generally to all measurements. This is not only the case with speeds. This is a general problem of measurement. We move away from speed and do this for a length. Then the examples become a little clearer.

We can take a measurement if we have at least two measuring points. This is clear in the case of length. We cannot determine length with just one measuring point. Nor can we determine speed or electrical charge. However, the second measuring point is not always immediately obvious to us. The other measuring point is often the zero point. However, this can also be of maximum value. It does not matter whether we take a measurement at a maximum or minimum value. We always need two measuring points to specify a value. A measurement is a comparison. In our case, these were the two boxes. Then we can measure the difference.

We want to specify an absolute value. This is a value that must remain the same for any observer. Then we need a measuring point that is identical for all observers. Intuitively, we always equate this with the zero point. This means that as soon as we can define a general reference point for measurement for all observers, a principle of relativity is no longer possible.

Within a principle of relativity, we can agree on the measured value of a difference. We call this an invariant quantity. However, the measuring points that led to this invariant quantity must not themselves be “invariant.” The measuring points must then shift. These must be explicitly different, otherwise we do not obtain a principle of relativity.

Let’s rephrase the fundamental question: When can we only determine a difference? To put it bluntly, when we have lost the zero point. We are then unable to specify an absolute value. We no longer know a universally valid reference point. This necessarily results in a principle of relativity. The only information available is differences. It follows that this view must always be symmetrical between the objects. In the case of a difference, it must not matter from which object we start the measurement.

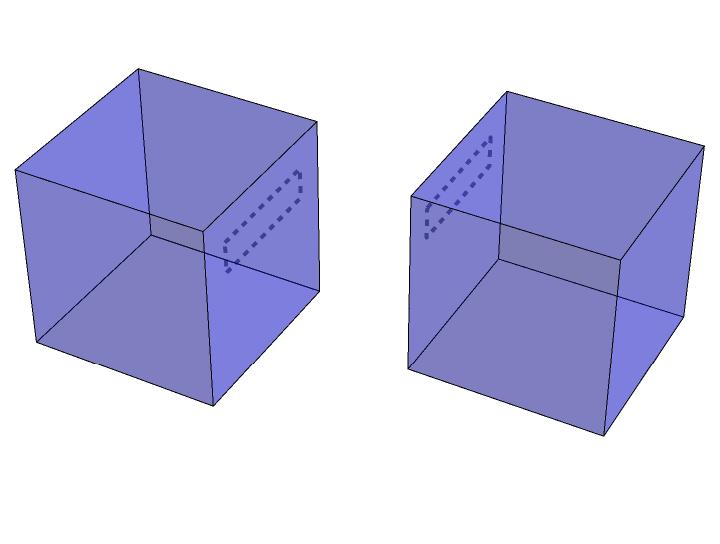

We have two lengths. We cannot determine the absolute values of the lengths. The zero point, the reference point valid for all observers, is not recognizable. The only recognizable features are the two red edges. We obtain a difference. In order to assign a value to the difference, we simply set the zero point on one of the red edges. In the case of a speed, we simply set a speed to zero. We can set the zero point arbitrarily based purely on mathematics. We do not know the “real” zero point. Intuitively, we select one of the edges. We obtain a symmetrical and relative measurement of the two objects in relation to each other. We cannot obtain an absolute value. Everything should be clear up to this point.

For an absolute value, we could also specify a maximum value. This is just as good as zero value. We have not yet discovered a maximum value for a length. In Galileo’s time, this did not apply to speed either. Why should there be a maximum speed? There was no reason for it. So, it was sufficient to remove the zero point. Here comes the trick we need to remember. For Galileo, there was a zero point, absolute rest. However, we cannot distinguish this zero point from a straight and uniform motion. This means that the zero point can be set arbitrarily by the observer. Then you set yourself as the zero point.

Important: For Galileo, there is then also no greater or lesser for the values. A difference can also be a difference between a long and a short rod. However, to measure the length of a rod, we need a zero point. There is only one reference point for all absolute measurements. But that is precisely what is missing. It follows that, according to Galileo, there is always only a 100% symmetrical view between the objects.

The principle of relativity is so simple and logically clear that Newton also used it as the basis for his description of physics. Newton and Galileo agreed on the principle of relativity. Based on the definition of his axioms, we can best recognize Newton’s view of the principle of relativity. Newton has three axioms:

The strange thing about the axioms is that the second axiom seems to contain the first axiom. If we do not exert any acceleration, then there is no change. If we have no change, then a body remains force-free and thus at rest or in a straight and uniform motion, since there is no change. Why this duplication? Because it is not a duplication. The first axiom is the shortest and most beautiful description of the basis of a principle of relativity. At least as it was understood until Einstein. If you like, Newton included the principle of relativity as a postulate.

Newton did not do this as in today’s textbooks on SR: Postulate, the principle of relativity applies. The crucial point in Newton’s statement for us is that a force-free body can be at rest or in a straight-line and uniform motion. There is no way to distinguish between the two. He stated the reason for the principle of relativity. The general reference point for velocity, the zero point, is no longer valid. Newton explicitly includes the state of rest. Like Galileo, he assumed that this exists but is not detectable.

After Newton, the world was okay for about 200 years. Until James Clerk Maxwell came along. He achieved a feat like that of Newton. Newton brought together all the individual loose ideas on classical mechanics into a single, almost completely consistent theory. Maxwell did this with the individual parts of the description of electricity and magnetism and, with electrodynamics, also delivered a complete, consistent theory.

However, this has given rise to a problem we are familiar with. The two great theories, which were supposed to describe the entirety of physics at the time, did not fit together in some places. Somehow, the problems keep repeating themselves over time.

Let’s pick out two important points.

c\space =\space \sqrt{\cfrac{1}{\epsilon_0\space *\space \mu_0}}

The problem with this description is that \epsilon_0, , the electric field constant, and \mu_0, the magnetic field constant, are both unchanging natural constants. This is independent of the state of motion. Therefore, c must also be an unchanging natural constant. The speed of light must always be the same, regardless of the reference system. All natural constants must be identical in every reference system. These reference systems are inertial systems. This allowed them to move uniformly and in a straight line. How can the speed of light remain the same when observed from any inertial system?

At that time, Newton was the demigod of physics. Therefore, a solution was sought that had to correspond to Newton’s description. Even Maxwell understood the problem in such a way that there must be something unknown in electrodynamics for the principle of relativity to work again at the speed of light. We did not obtain a new zero point, but we did obtain an absolute maximum value. This is a clear reference point for every observer. This means that the principle of relativity no longer works.

One solution was the ether. It was already suspected that this maximum speed belonged to light and that light was therefore an electromagnetic wave. So, this wave description of light had to have a medium, like waves in water or sound in air. This medium for the propagation and excitation of electromagnetic waves was supposed to be the ether. Then the speed of light only has this absolute value of speed in relation to the ether. Galileo’s principle of relativity would thus be saved and only incorrect in relation to the ether. The ether then had to be the absolute zero point, i.e., the resting point, for the speed of light. The ether always had to have an absolute value, but not in relation to the observer’s space (spacetime did not yet exist).

addition, this ether could not be proven in any experiment. In particular, the experiment by Michelson and Morley in 1881 and 1887 caused major problems for the ether theory. The aim was to find an ether via the movement of the Earth through the ether. The result was negative and remained so to this day.

The rescue of the ether, only for this experiment, because the other problems remained, then came from Hendrik Antoon Lorentz. A new transformation was developed, the Lorentz transformation. This is structured in such a way that the existence of an ether is compatible with the Michelson-Morley experiment. To achieve this, however, the length in the direction of motion had to be shorter and time had to be slower. Length contraction and time dilation were already known before SR. For Lorentz, length contraction was only present in the electromagnetic field (ether) and time dilation was a purely mathematical aid.

Mathematically speaking, Lorentz had found a solution. Now here’s the funny thing. It was developed for an ether theory. This means that the Lorentz transformation only works with an absolute zero point and the corresponding absolute velocity. That should be clear. If an absolute velocity is assumed, then there must be an absolute reference point. Here, it was the zero point in relation to the ether.

But now, finally, to our joker. In my view, SR actually has several fathers. There were already several other developments by several people on this topic. Einstein contributed the final brilliant idea here. In my view, he made the following assumptions for the development of SR:

These points are sufficient to arrive at SR. We can use them to construct the following logic:

This almost gives us SR. For a clear justification of length contraction and time dilation in spacetime, which was a very bold assumption in Einstein’s time, Einstein argued extensively with simultaneity in spacetime. Better said, with the simultaneity that no longer exists. To do this, he had to make an additional assumption that had not been made before. The speed of light is not only constant, but also maximal. According to Maxwell, c is simply constant for electromagnetic waves. For Einstein, this now had to be maximal for any effect in spacetime. Only with this extension does SR result. Therefore, this condition looks like a “foreign body” in the theory to many others.

Due to the maximum speed, there can no longer be simultaneity for an effect from one spacetime point to another spacetime point. The effect always requires time between the spacetime points. We will now develop another approach that is more suitable for the DP and avoids the discussion of simultaneity for length contraction and time dilation.

If we follow this logic, then in my opinion we fail to recognize the joke in the matter. The same applies to the argument of simultaneity, which we will not pursue further here. But this is exactly how it is explained in textbooks. That is why almost no one notices it. Einstein did not simply change Galileo’s old principle of relativity. He constructed a completely different principle of relativity. The basic assumptions of the Galileo transformation and the Lorentz transformation are mutually exclusive if we no longer have ether.

What did Einstein do that makes me think he’s such a joker? His two principles are:

The two principles are mutually exclusive. This is what I meant when I said that the Galileo and Lorentz transformations are incompatible in their basic assumptions.

No problem, then Einstein is right and Galileo is wrong. Unfortunately, it’s not that simple in DP. We will develop a third concept as an argument for a principle of relativity. This concept follows the assumptions of Galileo and Newton more closely. However, Einstein must also be right, even though the approaches are mutually exclusive. For 120 years, SR has been flawless in all calculations related to experiments. It cannot be wrong. The different approaches to relativity must be mathematically identical under certain circumstances. This feat can only be achieved if all deformations of spacetime are a change in the definition of spacetime geometry.

This immediately raises the crucial question: Why does SR work at all? It never results in a principle of relativity. But it does, just not in the way everyone imagines. The two theories of relativity compare fundamentally different things. We can only understand this if we look at the basics. The chain of argumentation in textbooks always starts with Galileo and then moves on to this principle of relativity, modified by Einstein, to SR. Here, I am not sure whether Einstein himself recognized this difference. By doing this, we simply transfer Galileo’s idea of the principle of relativity to SR. SR is the special theory of relativity. It sounds as if this is just a special case of relativity. This approach is wrong. What do we need to do to clarify this? Ask the next fundamental question.

What kinds of objects are compared in Galileo’s principle of relativity? First, our two boxes. The boxes in relation to what? Only to themselves, since we have lost the reference point. The reference point in relation to what? The surrounding space. With Galileo and Newton, we can only talk about space. A spacetime with a dynamic definition of length and time was not yet known here. In general terms, this means that we compare the states of motion of different objects in identical space. This fundamental structure, which has never been questioned, is now transferred to SR. As we have learned from the principles, SR cannot do this. SR has to do something else.

I will spare you the next round of questions and give you the answer right away. SR is still a principle of relativity. It must compare objects. However, these are not our boxes in spacetime. SR compares two fixed spacetimes, each of which is assigned to a box. In SR, we do not compare two objects in one dynamic spacetime. We compare two static spacetimes that we assign to each object. A comparison, yes, but not actually the comparison we want.

A brief aside from my personal experience. When I was working out these fundamentals, I naturally discussed them with others. Sometimes in personal conversations or in a physics forum. In the process, I received the following interpretation of SRT from different people:

The crucial point here is that if I had put these people in a room and given them a purely mathematical task on SR, I am 100% sure that all of them would have come to the identical and absolutely correct result. They would have congratulated each other and claimed that we all understood everything identically because we could calculate it correctly. That is the difference between calculating and explaining.

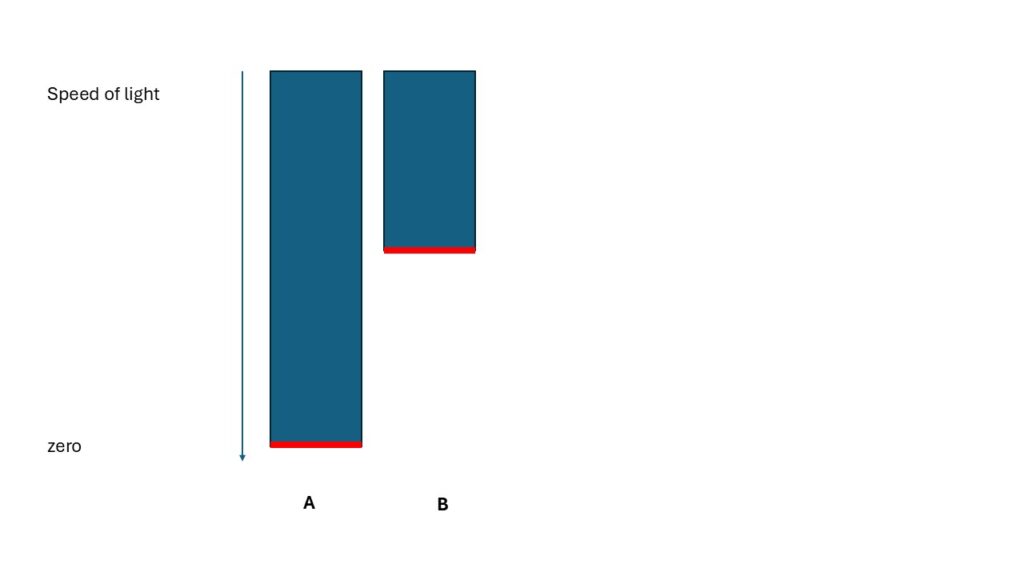

Can we create a principle of relativity between spacetimes? Let’s take a look at a comparison according to SR.

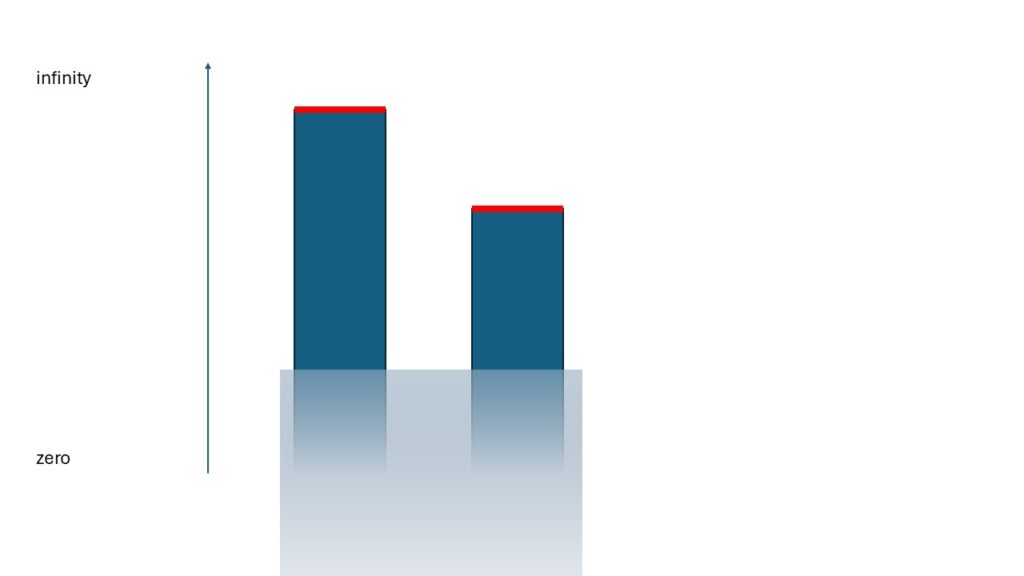

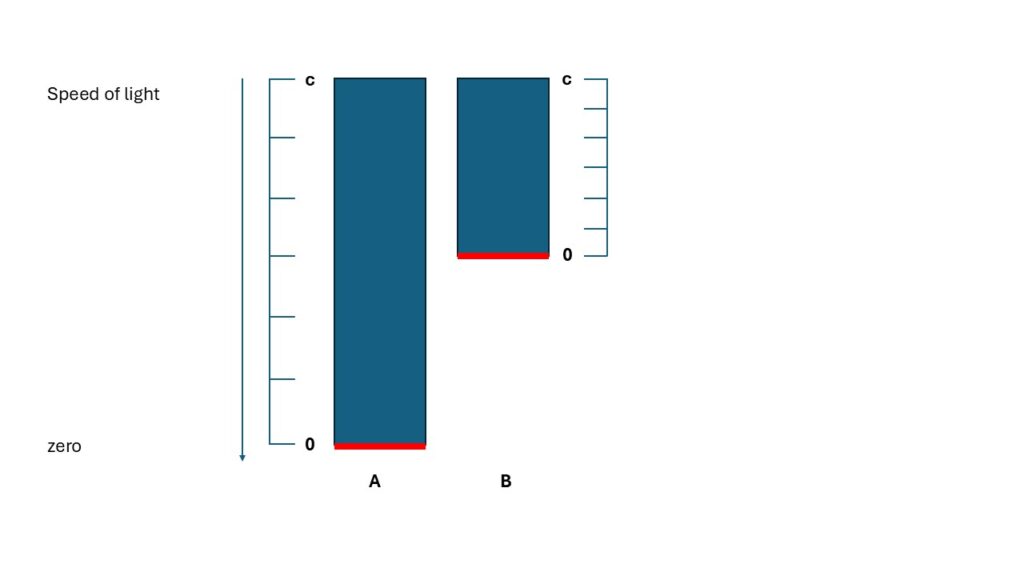

Here we see two lengths again. Both start from the zero point with a different length relative to each other. Both lengths start from the zero point in their spacetime. Then we need the end point, the speed of light. This must be identical for all of them. Otherwise, a comparison between different geometries is not possible. This is precisely where a crucial point in SR lies. If we have a dynamic geometry, we need at least one absolute reference point so that we can compare the geometries at all. The speed of light takes on this role. The speed of light, as an absolute reference point, does not “mess up” relativity for us; we absolutely need it. We need the zero point in every geometry so that we have a uniform second “edge” for measuring differences. This is why the Lorentz transformation works with the absolute values for the rest point and the speed of light. We absolutely need these points so that we can compare spacetime geometry at all.

To do this, a different length division must be selected at B. The number of divisions must be the same in both cases. From zero to the speed of light, the absolute value should be identical for all. This comparison is again symmetrical. We could set the rest frame at A and B. This allows A and B to be absolute values in spacetime A and B. That is not a problem. No comparison is made in the respective spacetime. Spacetimes A and B are compared. We see that the principle of relativity also works between differently defined spacetimes.

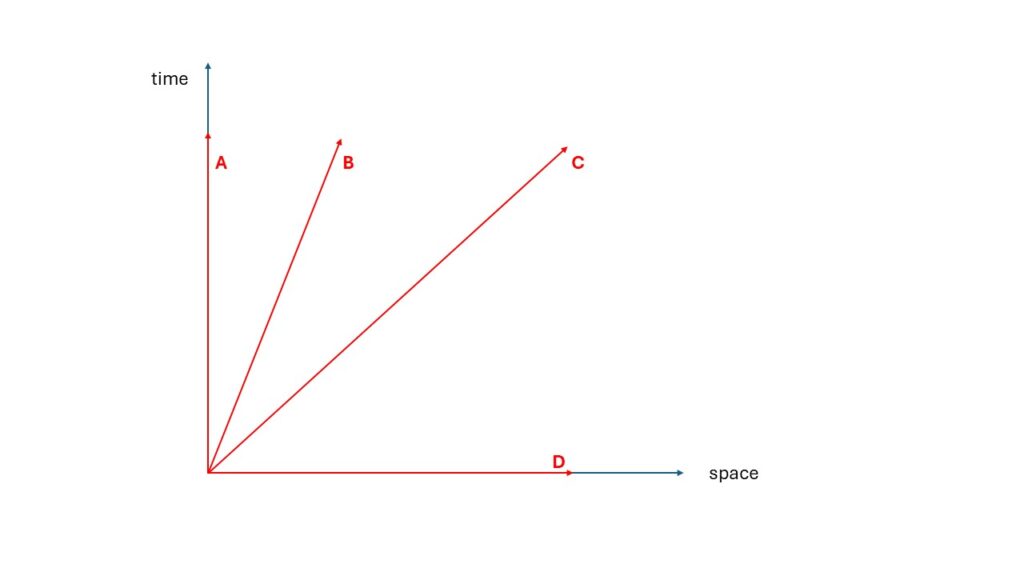

Then our condition must work for the spacetime itself and not just for an object in spacetime. The spacetime relative to each other must not have an absolute reference value. To understand this, let’s look at the structure of a normal spacetime diagram.

Let’s look at the given possibilities:

In all cases, we move, even if only in time or only in space. What does not exist explicitly for spacetime is rest. Even if no object exists in spacetime and only spacetime itself exists, time still passes. In the mathematics of SR, this is also a movement. Spacetime as an independent object knows no state of rest. Fortunately, we have lost the zero again. Within spacetime, we simply set a resting point and generate absolute values. This is not possible for spacetime itself.

But what about maximum speed? We have the speed of light. Yes, but it is now absolutely necessary in order to make a comparison possible at all. If both spacetimes have different geometries, there must be a common reference point for comparison. Otherwise, we would not even be able to specify a difference.

For spacetimes, we can only define one reference point, the speed of light, and we urgently need this so that we can make a comparison at all. We obtain a genuine principle of relativity between spacetimes due to variable geometry in the spacetimes. This is the SR. This allows us to solve several problems at once. We can use it to explain why the twin paradox is so difficult for SRT, which we will do in 4.11. We can clarify a point that I have called cherry picking, which we will do in 4.10. We can explain why SRT fits better with QM than with ART in 4.12. We will see that with this interpretation, SRT really makes sense.

One question remains unanswered by Galileo’s principle of relativity. Can there be a greater or lesser in SR? In SR, we only recognize differences. Anyone who wants to measure this difference must necessarily set themselves at the zero point. With Galileo, we only had one possible reference point. That had to go, otherwise we would not have a principle of relativity. That is not the case with SR. We have a zero point and the speed of light. But we need those to be able to determine the difference. In the first approach, no greater or smaller comes out. If we want to have such an indication, we explicitly need another reference point between the spacetimes. We will see that the twin paradox provides us with this and that we can therefore determine a younger and older. This is only possible in time and not in space. However, we will discuss this in the appropriate section.

Before resolving all these points, we need to take a different approach, which will make these solutions even clearer. First, we need to establish a new perspective on the DP. This should combine Galileo’s principle of relativity, everything in one spacetime, and Einstein’s principle of relativity, comparison of spacetimes. Believe it or not, we already know all the necessary components for this.

We are not introducing a new name for this variant of SR. The old variant according to Galileo and Newton is simply the principle of relativity. The variant according to Einstein is SR, and we have now recognized that it is actually very special. For our new variant, we will simply stick with the name SR. Since SR is mathematically identical in both variants, we do not need new names.

What do we want? We want a comparison of two objects in a single spacetime. Because that is what we actually mean when we talk about a principle of relativity (Galileo). Then we must be able to deal with different geometries of spacetime in a single spacetime without having to use an absolute value. As mentioned at the beginning, we do this with our spacetime density. This must contain all the necessary properties from both variants. Again, it sounds very difficult, but it’s simple. We have already incorporated this into our approach. We do not distinguish between stage and actor. A spacetime density is always also spacetime itself. This means that the property only needs to be present, and then it is automatically there in both variants. We can also divide the variants differently. In Galileo, the actors are compared on a stage. In Einstein, the stages are compared. We no longer recognize this difference

What makes life easy for us now is that spacetime density is always energy, geometry, and state of motion in one.

If we want to compare two spacetime densities, there must be no zero point for spacetime density. We discussed this in detail in Chapter 3. A spacetime density of zero cannot exist. Otherwise, the spacetime point does not exist in spacetime. That concludes this section. By definition, there can be no zero point for spacetime density. Since the state of motion itself is spacetime, there can be no resting point in a spacetime density. Contrary to Galileo and Newton, we cannot simply fail to distinguish the resting point; by definition, we have no resting point

With higher momentum, we have more spacetime density. I can relate this to the speed of light. For spacetime density, the limit is infinite. This means that there is no limit value. However, for the state of motion, there is an absolute value, the speed of light. This provides a reference point. There should be no principle of relativity for speeds in DP. We are not giving up that easily.

We have the speed of light in spacetime. This is clearly defined by geometry and is therefore an absolute value. The statement is correct. Nevertheless, we have no reference point in spacetime. We only have one between spacetimes. We use the same trick here as Newton did with rest. There we had rest or straight and uniform motion. Since we cannot distinguish between the two states, the zero point has been eliminated. Something similar happens with the speed of light. It is always identically far away for every object and therefore cannot be used as a reference point for a measurement within a spacetime. That was Einstein’s basic idea. However, it is a postulate. We cannot use it as such. We have to derive this constancy of the speed of light. We will do that in the next section.

We discussed the existence of the speed of light in detail in Chapter 3. As a structural element of spacetime, it is necessarily given by the spacetime boundary. However, this is only the first step. We have an identical condition. This does not explicitly generate the constancy of the speed of light.

In the second step, we must show that, despite this condition, we have an identical distance to every object. There are two possibilities for this. One of them is wrong. Unfortunately, the wrong possibility is very often used. Let’s take a closer look at the two possibilities.

We already discussed this topic in relation to Planck’s constants. Speed is a fraction \frac{Länge}{Zeit}. This means that there are an infinite number of values that lead to the same speed. In SR, the dimensions of length and time change identically. This means that the value of the fraction does not change overall. Length and time become smaller and larger to the same extent. Speed therefore does not change and must remain the same locally.

Part of the argument is correct. We cannot detect any change. The second part, that this happens because the speed does not change its value as a fraction, is unfortunately incorrect, even though it appears to be correct.

The best counterexample is the Shapiro delay, as it has been well confirmed experimentally. We will discuss this in more detail in the next chapter on the equivalence principle of GR. What is important for us now is that light in a gravitational field can also move slower for an external observer. Locally, however, light must again travel at c. Here, length and time change in opposite directions. This never results in a locally constant speed over a fraction. Although we are in SR, we need a more general solution that also works in the context of gravity.

The first thought was that we can detect the changes, but they cancel each other out. For the constancy of the speed of light to work, we must not be able to detect a change in the components of spacetime locally in the first place. Then it is irrelevant what the environment looks like or how the spacetime components behave in relation to each other. We achieve this by defining the geometry of spacetime density. Since everything in the universe is spacetime density, the local constancy of any given quantity is also achieved.

Let’s start with length. The change in the space component can be whatever it wants; we can never detect it locally. The meter as a reference size is not squashed. It is defined differently locally for the object. If a spaceship flies at approximately 86% of the speed of light, then the meter is only half as long for us in the direction of motion. However, there is no physical way to determine this inside the spacecraft. Absolutely everything in the spacecraft now has a new definition of length. A meter always remains a meter locally. We cannot detect the change locally.

Time behaves identically to length. The second is now defined differently. There is no way to determine this. But we have defined time as a measure of distance to the spacetime boundary. The spaceship has moved closer to the spacetime boundary. Yes, that’s right. Locally, we cannot determine this either. We would have to be able to detect length contraction or time dilation in order to determine this. We do not have this possibility. From the perspective of the spaceship, it has not moved any closer to the spacetime boundary. Therefore, locally, everything remains as it is.

Locally, it is not possible to detect a change.

Locally, no approach to the spacetime boundary is detectable. It must always remain identically distant. This results in the constancy of the speed of light.

This “no change detectable locally” does not only imply the constancy of the speed of light. It also explains why, according to SR, we can place everything in a rest frame. The distance to the spacetime boundary does not change locally and there is no zero point. This means that every object can be considered at rest without acceleration. If the definition of length and time does not change, then we always have an initial frame. Every local observer has a good definition of length and time. These may differ locally from observer to observer, but locally, each observer has a unique definition and thus an inertial system. This is the reason why we can work with the idea of an inertial system in the first place. This is the connection between SR, comparison of spacetime, and the old principle of relativity, comparison of objects in spacetime.

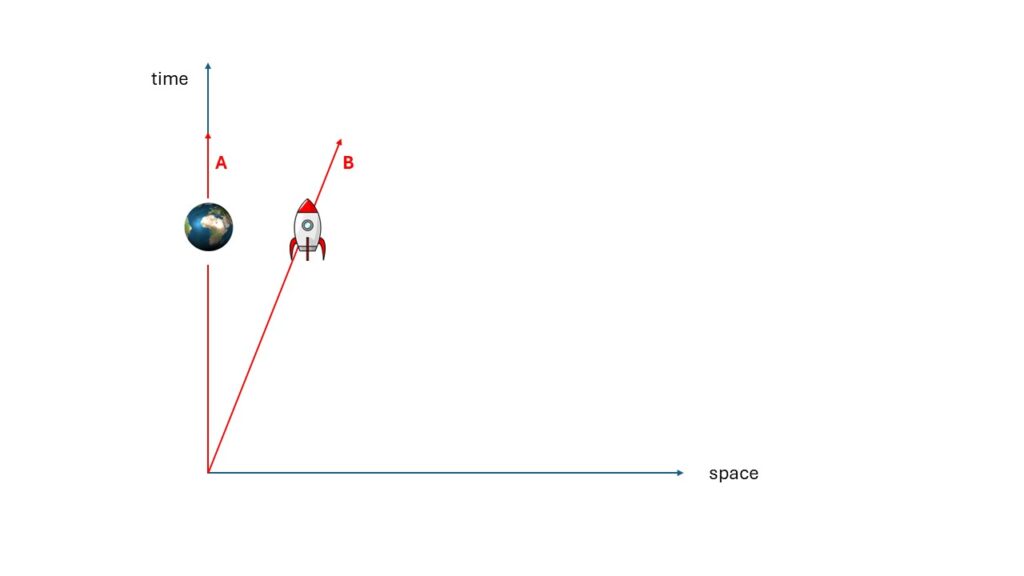

Let’s look at the principle of relativity in DP using an example. We’ll use the classic example of a person on Earth and a person in a spaceship moving away from Earth

Then we have two views to discuss. One from Earth and one from the spacecraft. We’ll start with the simple case.

Here, SR and DP agree on the perspective. Therefore, the case is simple. The person on Earth experiences no change in their state of motion. Thus, the spacetime density remains identical. For SR, this person simply remains in the rest frame. The spacecraft is accelerated and thus actually acquires a higher spacetime density. The spacecraft experiences length contraction and time dilation. This can be measured in real terms from Earth. However, nothing can be detected in the spacecraft itself; there is agreement on this point.

Length contraction and time dilation are real physical changes to the spacecraft. They are not just a point of view. It is precisely this statement that leads to the assumption that spacetime density is not subject to any principle of relativity.

At first glance, everything seems very simple in SR. Once the spacecraft has completed its acceleration phase, it can claim to be at rest. The Earth has accelerated and is flying away from the spacecraft. The Earth must now necessarily be subject to length contraction and time dilation. A completely symmetrical view.

This is precisely where the problems begin in understanding SR. The acceleration phase has taken place solely and exclusively on the spaceship. Why should the Earth now be different than before? The Earth is not sufficient in this consideration. In the direction of motion, the entire universe must have accelerated. No, definitely not. The universe does not change just because a spacecraft somewhere had an acceleration phase. This is the best way to see that SR does not compare two objects (Earth and spacecraft) in one spacetime. Depending on the perspective, the objects are assigned a suitable spacetime, which always ranges from zero to the speed of light. Then the comparison of the spacetimes is made. Therefore, from the perspective of the spacecraft, the entire universe must have undergone a change. Only the spacecraft had an acceleration phase and received this new definition of spacetime. However, it is a definition of a complete spacetime.

However, SR only recognizes one direction in comparison. The other object always has the “smaller” definition with time dilation and length contraction. In a principle of relativity, there should only be a difference and no specific direction. This in turn results inevitably from the approach with the Lorentz transformation from an ether theory. This assumes a zero point that is identical throughout the entire universe. Therefore, in SR, we obtain this preferred direction in the comparison.

In DP, only the spacecraft may have the higher spacetime density. Only there has acceleration occurred. Then the spacecraft has a changed definition of geometry. The spacecraft recognizes, just like Earth, that there is a difference in the definition of geometry. Only this difference is recognized. Even if it is clear to the spacecraft which one must have the higher spacetime density, we cannot measure this from inside the spacecraft. The spacecraft now has a different definition of geometry. The spacecraft can now only recognize all observations to the outside world using its definition. Let’s proceed strictly according to SR. Then the spacecraft is at rest and the Earth has accelerated. What does it look like for the spacecraft according to DP? The Earth has definitely maintained its speed. But so has its definition of spacetime. The meter on Earth is defined as longer than the meter in the spacecraft. Then, from the spacecraft’s point of view, Earth creates more length at the same speed. This means that, for the spacecraft, Earth must have accelerated. Not just Earth, but the entire damn universe. Only the spacecraft has changed its spacetime density. This means that, for the spacecraft, the entire universe must necessarily undergo a change.

DP only makes a spacetime change to the object that has also had an acceleration phase. But then there is a global change for the object. SR does this by always assigning a complete spacetime to each object. Then the DP and SR perspectives seem to be identical. So why all the fuss? Because they are not identical.

In DP, the spacecraft actually has a higher spacetime density. In SR, we cannot determine this. Only a symmetrical approach is possible. In DP, it is clear that length contraction and time dilation are only local phenomena. In SR, these are always global from each perspective. We will clarify these two points in the next two sections.

According to SR, time dilation and length contraction always occur identically and are physically measurable throughout spacetime. But then we encounter a logical problem. Mathematically, everything is clean because it is symmetrical. Logically, however, it becomes critical. The approach from DP solves this problem very easily.

As always, I have arbitrarily named this problem “cherry picking.” When I sit in my chair and write this text, I have a defined time and a defined length between my two hands in front of me. Now muons are continuously approaching this length from all sides of the Earth’s atmosphere. Since muons are very fast, the length must be different for these particles, depending on the angle to my hands. We cannot really imagine this.

Almost all discussion partners make a rather idiosyncratic distinction here. Each muon must have a different time than mine. These are objects that are different from my hands. They can have different time courses. Since time remains a mystery, this is simply accepted. This is a good thing, since time dilation has now been verified with impressive accuracy through experimentation. Hack on it.

According to SR, however, the length must also change physically. Time dilation only occurs with length contraction. Time dilation is measured experimentally, so conversely, length contraction must also occur physically. This means that the distance between my hands must constantly change, depending on the angle at which the muon moves toward my hands. Almost no one accepts this. Many abandon the path of virtue and go for what is logically understandable. Length contraction is only one point of view; time dilation is real. From a logical and mathematical point of view, this makes no sense in SR. Either both are just a point of view, or both are physically measurable. We are certain about time because it is measured. When it comes to length, we don’t want to accept it, just “cherry picking.” The problem arises because SR always assigns a complete spacetime. In fact, this does not make logical sense. But since mathematics works very well => shut up and calculate.

In DP, it is clear. It is always a real physical effect. However, this is only local to the object. From the object, the appropriate view of the rest of the universe, which is unchanged according to the local definition, then results. Cherry picking is not necessary.

Sorry, but if we’re going to chew through SR, we can’t leave out the twin paradox. In particular, this paradox allows us to clarify the problem with information about greater or lesser spacetime density. Most other paradoxes (e.g., the garage paradox) are rather uninteresting. They can always be explained by the symmetrical view of non-simultaneity. In the twin paradox, however, there is no symmetrical result. There must be a reason for this.

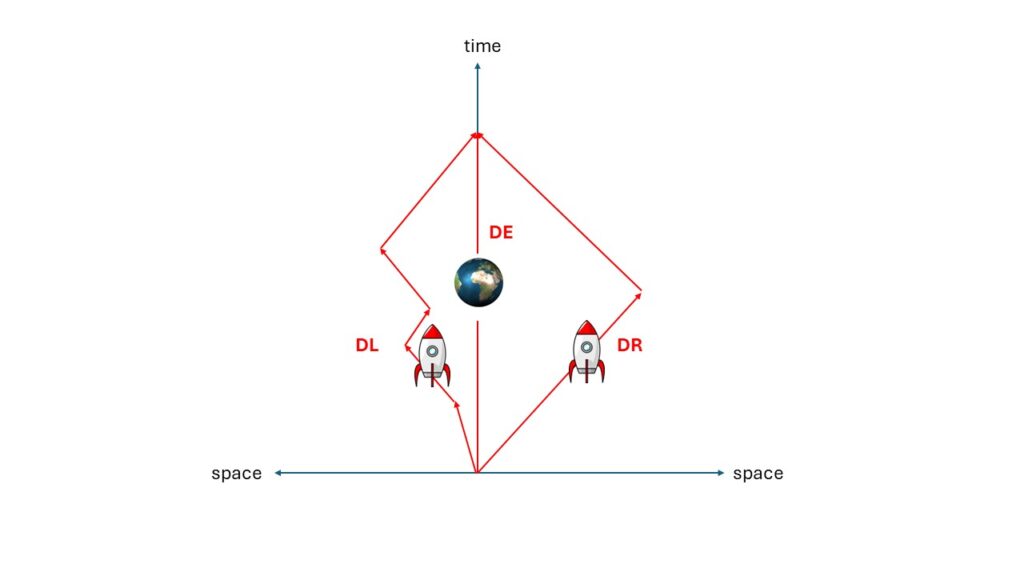

In mathematics, there is no difference. Even SR concludes that the twin in the rocket is always the younger one. This is also the expected result in DP. In SR, however, it is not clear why this is the case. Arguments such as symmetry breaking are often used to explain this. For a better understanding, let’s extend the twin paradox to triplets.

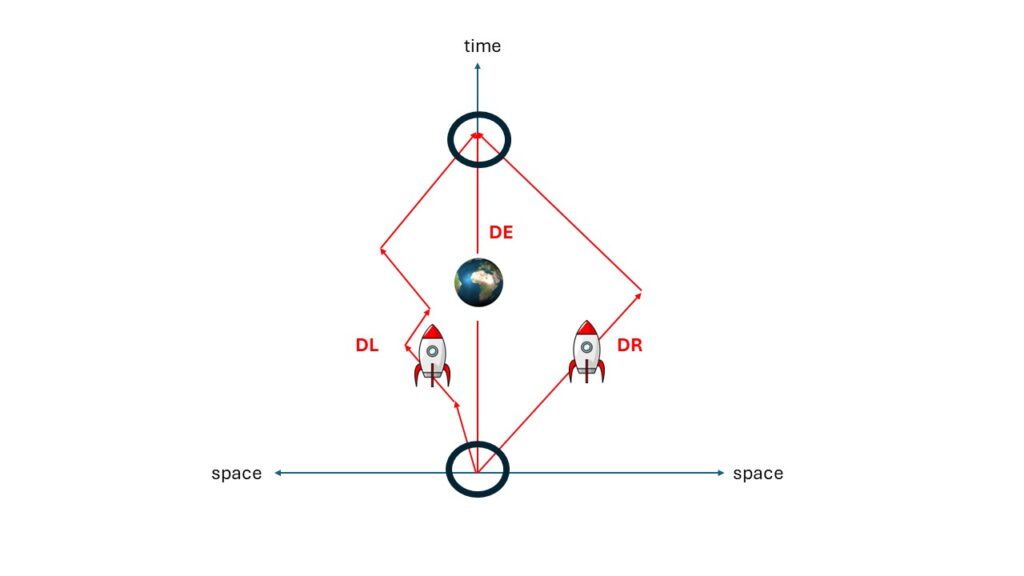

There is a triplet on the left (DL), a triplet on the right (DR), and a triplet on Earth (DE). DR has a single destination, while DL visits several locations. DE remains on Earth and only moves forward in time. What may not be 100% clear in the image is that the total distance traveled by DL and DR should be identical.

The result is clear. The triplets are the same age at the starting point. When they meet again, DL and DR are the same age, as both have traveled the same distance through spacetime, and DE is older than the others.

In DP, this result is logically to be expected. Only DL and DR experience an increase in spacetime density. Only DL and DR can experience time dilation compared to the starting condition. It does not matter in which direction the time dilation occurs. Only the sum of the time dilation, i.e., the distance traveled, is relevant in the end. Here, there is information about younger and older or smaller and larger spacetime density.

This is not clear from SR. SR is always symmetrical. This means that between DE and DL, the other must experience identical time dilation and there should be no difference. However, the result looks different. Why does this happen? I have not yet read a good explanation for this. The most common explanation is the most obvious one. If symmetry no longer exists, then it must have been violated. Because there is nothing else, the culprit is quickly found. The evil, evil acceleration. This must break the symmetry. Then come even worse statements, such as: “SR cannot handle acceleration.” What nonsense. SR can only and exclusively do nothing with gravity. Any type of classical acceleration can be incorporated into the diagram or calculations with 100% accuracy.

So, now calm down and tackle the solution. If the information is not already available, we cannot obtain it. We cannot generate additional information. The information must always be contained. In DP, we always have this information. We just cannot determine it in SR. It can only be extracted under certain conditions. That is the correct approach.

It can’t be the accelerations. We have expanded the twins to triplets to make this visible. We could also let DL fly through spacetime even more “back and forth”. If the sum of the distance traveled in spacetime is identical, DL and DR are identical in age. The number and direction of the accelerations are irrelevant. Acceleration is only necessary so that there is a change in spacetime density and the triplets can meet again.

What many people don’t notice is that in the classic twin paradox, the twin in the spaceship makes two symmetrical breaks. The first when he takes off from Earth. The second when he takes off again from his intermediate destination. Then the first symmetry break is a “good” one, because everything is still symmetrical, and the second symmetry break is a “bad” one that ruins everything. With good and evil do not work in physics. That is poor reasoning.

Let’s return to the basic elements. When did we have to switch from an absolute value to a principle of relativity? When we lost the reference points for measurement. If we want more information, there must be a reference point again that can provide this information. The image again with the two important points.

What is special about this paradox is the starting point and the end point. The starting point is identical for everyone in spacetime. The end point has remained identical in space and has shifted in time. It should be the identical spacetime point for each of the triplets. Within the principle of relativity, we have created an additional reference point for measurement. This gives us all the information about space and time that deviates from this reference point in the principle of relativity. Then, even in SR, one comes out younger and one older.

In Galileo’s theory, there is no smaller or larger. Not because he did not yet know about spacetime, but because there is only one reference point for everything, the zero point. In order to determine larger or smaller, we would also have to use the zero point in Galileo’s theory. However, this point must no longer be recognizable, otherwise there is no principle of relativity. Therefore, Galileo’s view is actually 100% symmetrical. This idea is transferred to Einstein’s SR and everything, except for the twin paradox, looks good. Only when comparing two spacetime points is a larger or smaller not explicitly excluded. That is allowed to exist. However, in normal cases, we can only recognize the difference between spacetimes. In DP, the local spacetime definitions are compared. Here, too, in normal cases, only the difference is visible, and everything looks symmetrical. However, we know that there is a larger and smaller. In SRT, as in DP, we simply need an additional reference point to obtain this information. The twin paradox provides this.

The last section in this chapter addresses the fact that the naming of SR and GR has, let’s say, been unfortunate, to say the least. We can no longer change the names. They suggest that SR is the little sibling of GR. I would like to contradict this here. From a purely mathematical point of view, I can still understand the statement. From a logical point of view, it is simply wrong. At this point, it is also clear that many people are good at calculating with SR. However, very few have understood SR. We will stick to the approach from DP.

What does GR do? It states how the spacetime components change due to spacetime density. This statement only makes sense within a single spacetime. Spacetime density is only the source. The actual statement does not concern spacetime density. We can see this from the fact that GR predicts a singularity. This is not possible with the approach of spacetime density. For GR, only the amount and distribution of spacetime density across the spacetime dimensions is of interest. Spacetime curvature must then compensate for this. GR makes statements about spacetime curvature. This applies to the surrounding area of spacetime density in a single spacetime. Several spacetime densities, spatially separated, can also exist there. This statement of GR concerns the surrounding spacetime.

What does SR do? In the old view, different spacetimes are assigned to objects and these are compared. This makes it appear as if SR makes a statement about spacetime. But SR cannot do that. Different spacetimes are compared. SR cannot make any statements about a single spacetime or a single object. We always need at least two objects, otherwise SR makes no sense. In DP, it becomes a little clearer. SR compares the local definition of the spacetime geometry of different spacetime densities. These are statements about spacetime density. Just because the rest of spacetime appears different from this definition, we believe that SR makes a statement about spacetime. Clearly, in DP, everything is spacetime, so every physical statement is a statement about spacetime.

SR makes absolutely no statement about the surrounding area of a spacetime density. It is only a comparison of spacetime densities. GR needs a spacetime density as a source of spacetime curvature. However, GR is not otherwise interested in spacetime density and only makes statements about the surrounding area. From this we conclude:

GR and SR result in two completely different statements.

SR is simply included in GR because, by definition, the principle of relativity in DP must be incorporated into all physical statements. Everything is spacetime density, and this is always subject to the principle of relativity.

What does QM do? It describes the “internal structure” of a spacetime density through low-dimensional spacetimes (fields). However, QM is only interested in spacetime density. Spacetime density knows no spacetime curvature. QM uses the surrounding area of spacetime density only as a “given possibility.” A low-dimensional spacetime density cannot determine whether this has spacetime curvature. This means that the surrounding spacetime is of no interest to QM. Therefore, SR and QM can be unified to a certain extent. Both look at spacetime densities and not at the surrounding area.

This concludes this chapter. In the next chapter, we will take a closer look at GR.