Everything consists of spacetime.

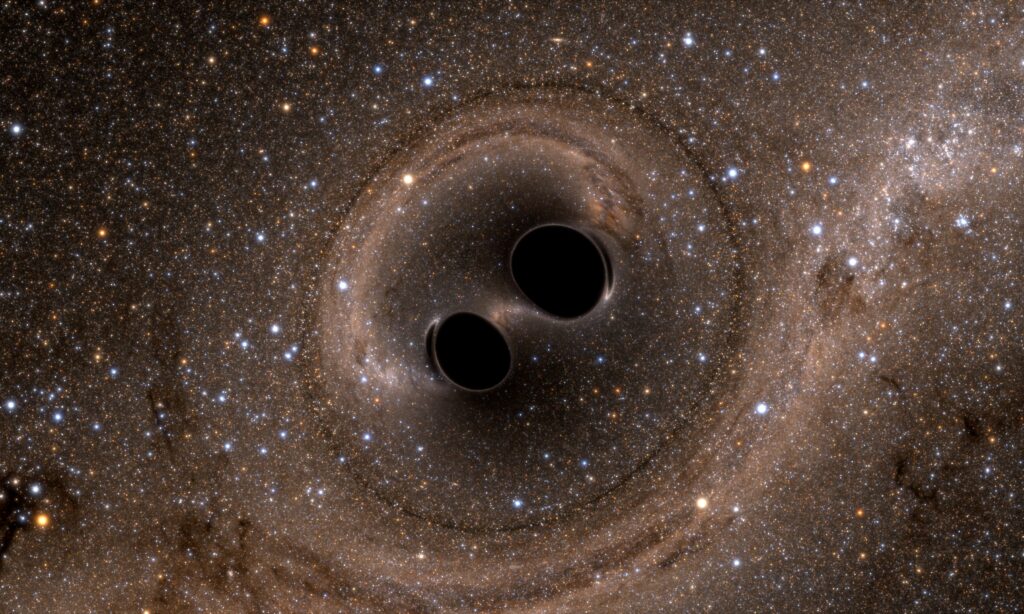

This concerns the development of our universe. It is all based on the new view of DP on GR. For cosmology, we will have to extend GR to higher- and lower-dimensional spacetimes. We define that the term “universe” always encompasses all these spacetimes. A spacetime is only a specific spacetime configuration. The universe is a collective term for everything.

In cosmology, we will connect the spacetimes across the dimensional boundary to form a universe. This means that our universe is not fixed to one spacetime, but rather to recursive spacetimes. We will show that each of these spacetimes is a potential field in itself.

We can specify what the Big Bang really was, but we cannot determine its true origin. We can specify an object for dark matter that is necessarily created in a kind of inflationary phase, but which is not a new elementary particle. Dark energy is no longer needed.

Here, too, there is a fundamental question that is too rarely asked, in my opinion. Why is our spacetime expanding? Unfortunately, the word “Big Bang” contains the word “bang.” Doesn’t that clearly imply that the object must also expand with the “bang”? We will see that this has nothing to do with a bang at all. Is it spacetime or, as described in textbooks, only space that is expanding? The field equations of general relativity show that a static universe does not work. General relativity does not allow for a static universe. Yes, but mathematics does not force any object to do anything. There must be a reason built into this mathematical model.

In addition, we will learn about further “deformations” of spacetime in this chapter. The picture is not yet complete. These deformations are not possible at all spacetimes. This depends on the number of spatial dimensions. We need all these ingredients to build a clean and closed picture for GR and the universe itself.

More importantly, we need to understand the concept behind cosmology well. The reason may be somewhat surprising. The concept developed here in cosmology, beyond dimensional boundaries, is the basis for quantum mechanics (QM). QM is a form of low-dimensional cosmology. QM cannot be understood without cosmology.

We have an approach with spacetime density and spacetime boundaries. Therefore, every n-dimensional spacetime volume has an infinite number of lower-dimensional spacetimes and at least one higher-dimensional spacetime. We will look at how these affect the different numbers of spatial dimensions. This approach will make it clear that QM and cosmology go hand in hand. Let’s keep it simple again and start from scratch.

This is very easy for us. We already discussed this in relation to the boundaries of spacetime. That was the discussion with the mathematical abstraction of a point. There can be no spacetime without a spatial dimension. That’s it. Spacetime without a spatial dimension will not be discussed further.

If we have one spatial dimension, then we always have a time dimension as well. Thus, a spacetime. In DP, there can only ever be one time dimension in a spacetime configuration, as this is the measure of distance to the spacetime boundary.

The problem with only one spatial dimension arises from GR. This cannot be represented in a spacetime with only one spatial dimension. The aim is to determine the deformations of the space and time components in relation to each other. With only one spatial dimension, no spacetime curvature can be determined. GR only starts with two spatial dimensions. Even if we could have a density and a curvature purely logically in only one spatial dimension, there is no low-dimensional spacetime for it. There can be no rest mass or elementary particles, since there can be no low-dimensional quantum mechanics. We have ruled out spacetime with zero spatial dimensions. However, these are the sources of spacetime curvature. Result: In a spacetime with only one spatial dimension, there can be no representation of spacetime density or spacetime curvature within this spacetime.

Does that rule out 1D? No, not quite. For us, 1D is usable and must be so. Contrary to GR, we can work with extrinsic characteristics. Extrinsic deformations have no effect in their own spacetime. We obtain a higher spacetime density in 2D when 1D has an extrinsic characteristic. In 2D, there is more 1D spacetime. This is identical to the discussion with the photon. Only one spacetime configuration deeper.

We will need this again in Part 3 for the description of neutrinos. In cosmology, it is important for us that a 1D spacetime cannot have a representation of a spacetime density and thus a spacetime curvature for itself. There can be no development within spacetime in 1D. Cosmology is not possible within 1D.

In 2D, we are “almost happy” from the perspective of GR, but only almost. We can map many things from GR in a 2D spacetime, with two crucial limitations:

We often imagine 2D as our 3D spacetime “squashed” onto a surface. This idea is completely wrong. No planet, no sun, no galaxy, and no life can form there. Something is either statically present or not. There are only three possibilities for a representation:

That’s all there is. This is not only a restriction from GR, but also from the limits of spacetime. The reason for this is simple. We do not have low-dimensional QM available in 2D. In order to be able to map elementary particles, QM must be available. In 1D, we only have the option of extrinsic mapping of a spacetime density in 2D. This gives us neutrinos. We have reached the end of the line. In 2D, we can only map neutrinos as elementary particles. Further representations of a spacetime density can only exist without a low-dimensional QM. We already had this with the limits of spacetime. Only a black hole is a spacetime density without a low-dimensional representation. Cosmology is the development of spacetime. A black hole in 2D cannot have any development because everything is static.

2D is therefore also out of the question for cosmology, as there is no development. In particular, 2D spacetime is very different from our 3D spacetime. The fact that 2D is completely static will benefit us later in QM.

Here is a small side calculation using the classic image of physics. We have Newton’s formula:

F\space =\space \cfrac{G\space *\space m_1\space *\space m_2}{r^2}

This results in a force and thus a change in spacetime density. The units of measurement are:

[m\space *\space a]\space =\space \bigg[\cfrac{l^3\space *\space m^2}{m\space *\space t^2\space \space l^2}\bigg]\space =\space \bigg[m\space *\space \cfrac{l}{t^2}\bigg]

In 2D, we have to make the following changes with our logic.

This results in the following for G:

G_{3D}\space =\space \cfrac{l_{P\space in\space 3D}\space *\space c^2}{m_P}\space \implies\space G_{2D}\space =\space \cfrac{l_{l_P\space in\space2D}\space *\space c}{m_e}

This results in the gravitational force in 2D with the units of measurement:

\bigg[\cfrac{l^2\space *\space m^2}{m\space *\space t\space *\space l}\bigg]\space =\space \bigg[m\space *\space \cfrac{l}{t}\bigg]

This is no longer a force, but only momentum. Thus, there is no acceleration and no change in spacetime density. Everything remains static.

We have finally arrived at our spacetime. We will see that 3D spacetime is something very special. We have two features from 3D that are “vital” to us.

With these brief considerations, it should already be clear that life, as we can define or understand it, exists only and exclusively in 3D spacetime. Since the rest of this chapter deals almost exclusively with our 3D spacetime, we can end this description here.

We cannot stop at 3D. We have black holes in our spacetime. These are a transition to a higher-dimensional spacetime. This makes us certain that our 3D spacetime is embedded in at least one 4D spacetime. That is both the good news and the bad news. Good, because it provides an explanation for the Big Bang. We will describe the Big Bang in the next section. The bad news is that this opens Pandora’s box. We are left with two major problems.

We have established at the boundaries of spacetime that every n-dimensional spacetime volume must have an infinite number of (n-1)-dimensional spacetimes. If there is at least one 4D spacetime, then there are also an infinite number of 3D spacetimes. If we look for an explanation for experimental findings from the cosmos, we get a new huge solution space. The 3D spacetimes could influence each other. If we look for a “culprit” for dark matter or dark energy, we can certainly build something from an infinite number of 3D spacetimes.

We do it here like GR. There, for reasons of economy, no higher- or lower-dimensional spacetime was explicitly assumed, and everything was placed in 3D spacetime. We will adhere to this principle when considering possible solutions. The first attempt at an explanation should always come from our spacetime. Only when there is no other option do we resort to the infinite number of other 3D spacetimes or to 4D spacetime.

If there is a spacetime with four spatial dimensions, then we simply need to increase our mathematics by one spatial dimension, and we can then calculate everything again in 4D. This still works with general relativity. Everything becomes a little more complicated, but it is possible in principle.

With QM from 4D, the fun stops. QM from our spacetime is already very complicated. It is just about manageable for two reasons, if one can say that at all.

A QM from 4D has 3D as its low-dimensional substructure. In 3D, there is an evolution of images in spacetime. Nothing remains fixed. The possibilities of the images in our 2D QM are only extrinsic manifestations and black holes. In 3D, there is everything that can be seen in our universe. QM from 4D must be incredibly complicated. In addition, black holes form in our spacetime. These are again a connection in 4D. This is the reason for the physical and mathematical worst-case scenario.

This is so far removed from anything I can imagine that I will leave it alone. This makes 4D as a solution completely unsatisfactory. However, we will at least shift one solution approach to an area that we cannot investigate. This is not really a solution, but merely a “shift.” However, DP dictates this path.

Of course, we cannot stop at 4D. Mathematically, recursion can go on indefinitely. How many spatial dimensions are there then? I do not know.

But we can make an estimate. If we want to have a QM mapping from an n-dimensional spacetime to an (n-1)-dimensional spacetime, then the spacetime density in the n-dimensional spacetime must not be a black hole. It follows that the total spacetime density of our 3D spacetime in 4D is not sufficient for a black hole (further discussion of this in the next section on the Big Bang). We must be a quantum of spacetime from 4D and not a black hole. Our 3D spacetime started as a 4D spacetime density.

In our spacetime, the Planck mass is the criterion for a black hole. The simplest representation of a black hole in 2D is an electron (Planck mass in 2D). The difference between 3D and 2D is already approx. 10^{22}. The universe has a total mass of approx. 10^{57} kg. The Planck mass in our spacetime is only 10^{-8} kg. The difference between 3D and 4D must therefore be at least approx. 10^{65}. This value increases extremely rapidly with each spatial dimension in a spacetime. If there is no longer enough spacetime density in a spacetime to represent the Planck mass, the recursion breaks down. I do not believe that we can escape from the single-digit range of spatial dimensions. We will learn shortly in the section on the Big Bang that our universe actually started with a much smaller mass. We make a mistake in extrapolating the mass in the universe if we believe that all the mass detectable today must have already been present at the time of the Big Bang. The error is particularly significant in the case of black holes.

We have gathered enough information to almost resolve the Big Bang. We cannot quite manage it because we have to “shift” the Big Bang into the realm of unsatisfactory solutions. We will definitely need 4D here. Let’s describe a Big Bang in 3D spacetime. We will see that a Big Bang has a lot to do with QM.

There are three fundamental problems with the Big Bang as described in textbooks.

There is no answer to any of these questions in the textbook. The development of the universe is simply (here far too simply) calculated back to Planck time and Planck length. Spacetime, energy in spacetime, fields, fluctuation, coupling of fields with spacetime, etc. must then simply be present. We do not want to start our universe this way.

Let’s try everything we have so far:

In fact, we also have to start with 3 spatial dimensions in the Big Bang. However, with only 3 spatial dimensions, we are in the same situation in DP as in textbook physics. Once again, we cannot answer the 3 questions. 3D spacetime is simply not enough for this. The textbook covers various fields. We have to resort to something else. Unfortunately, there is only one option left: the unsatisfactory 4D solution. Let’s try to solve the three questions.

As always, DP guides us in the right direction, as there are almost no other options. In order to obtain a spacetime density in an n-dimensional spacetime, there must simply be a spacetime density in an (n+1)-dimensional spacetime. Since the spacetime density represents spacetime itself, this “low-dimensional mapping” is a genuine creation of spacetime.

This makes it clear:

The Big Bang is a mapping of a 4D spacetime density as QM there onto a 3D possibility.

We exist in one of the 3D possibilities.

I know that this is not very spectacular for a Big Bang as a divine act of creation. However, within DP, this is the only possibility we have.

When we look at our bodies, we could previously view ourselves as almost divine beings. Every single elementary particle of our body, and there is a hell of a lot of them, has an infinite number of representations in low-dimensional space-times. We are made up of an infinite number of 2D and 1D spacetimes with black holes. Simply wow! Now comes the damper. From the perspective of a 4D spacetime, what are we? The best description is probably “nothing.” Our universe as a whole is an arbitrary spacetime density there. Whether there are elementary particles there, etc., I have no idea. As I said, that’s where I stop. QM in 4D has to be solved by smarter people. Only a black hole in our spacetime creates an effect in 4D again. Everything else is irrelevant for 4D.

What we can do is rule out one important possibility. We cannot be a black hole in 4D. Otherwise, there would be no lower-dimensional representation of this spacetime density. Since our universe exists, this is impossible. The same argument applies to the recurring idea that our universe is a 3D black hole, and we are at the center of the black hole. Even then, the spacetime density should not have a lower-dimensional mapping. I am sure that we are subject to QM.

Sorry that the Big Bang is so simple. Just a recursive image of spacetime density. We can now specify exactly what the Big Bang is in our spacetime. But we haven’t solved the basic problem. It has simply been shifted from 3D to 4D. Where does the spacetime density in 4D come from? I have no idea. I can’t even say whether we are just one possibility in 4D or whether we count as something real in a measurement there. I admit that this solution is very unsatisfactory. But it’s the only one we have.

For the “initial conditions” of the Big Bang, textbooks assume the Planck length and Planck time. Why is that? Presumably, it is assumed that there is no smaller length or time in our universe. When calculating the size of the universe backwards, one must stop here at the latest. Are Planck length and Planck time really good assumptions for the starting condition of the universe? Not for DP. There are two reasons for this:

Like GR, we assume continuous spacetime. There must be no smallest values for time or length. Otherwise, we would not have a continuum. Where does this lower limit come from?

In DP, Planck length or Planck time have no relevance on their own. It is the values we use for c, d, and h. However, these values always occur in combination. This combination of values is crucial. Thus, these are not the smallest units of space or time.

Where quantum physics and the textbook approach are identical is in the Planck length and Planck time as the smallest barriers for interaction. If you want to have limited interaction in these areas, then so much energy is required that the value of d is exceeded, and it goes into a black hole. Both theories agree that there must be no interaction of any kind in this area.

Let’s ignore the origin of spacetime and fields from the textbook approach in the Big Bang for now. We want the Big Bang to arise from fluctuation, symmetrical breaking, or something similar, as desired, but this is not possible with Planck quantities. Space and time are not defined at this level. How can an interaction in space and time take place there?

I understand that a lower limit is needed and, for lack of anything better, this one has been drawn up for now. Sorry, but that just doesn’t make sense. Can we specify something better in the DP?

We cannot calculate the initial size exactly. However, we can make an estimate again. Our approach for calculation is d, the dimensional constant. We are certain that our universe did not start as a black hole. Therefore, the spacetime density cannot have been too large. This allows us to specify a minimum size for the distribution of energy at the Big Bang, which cannot be undershot. We make the calculation a little simpler and not 100% accurate, as it is only an estimate. We take the reciprocal of d, which makes it a little more obvious.

\cfrac{E_P}{l_P}\space >\space \cfrac{E_V}{l_{wanted}}\space \implies\space l_{wanted}\space >\space E_V\space *\space dE_V is the energy of the vacuum. We assume that the reciprocal of d must always be greater than the right side. If the fraction on the right side is greater than or equal to the left side, a black hole would have to form. Then we substitute everything:

Energy in the vacuum approx.: 7.67\space *\space 10^{-10} Joule/m^3

d: 8.26\space *\space 10^{-45}

l_{wanted}\space >\space 6.338\space *\space 10^{-54}Oops! That’s smaller than the Planck length. We have also simply applied the energy from a volume to a length. We have to estimate the size for each spatial dimension. Our entire spacetime starts out small.

l_{wanted}\space >\space \sqrt[3]{6.338\space *\space 10^{-54}}\space \implies\space l_{wanted}\space >\space 1.85\space *\space 10^{-18} Meter

That is still very small as a lower limit. A proton is approx. 1000 times larger. However, the starting point is already 17 orders of magnitude away from the Planck length.

For me, this is one of the most important topics in cosmology. It is also one reason for accepting DP with spacetime density and spacetime boundaries. How can the fluctuation or symmetry breaking of a QM/QFT field influence spacetime?

Spacetime (or just space) is expanding. What about the fields? Do they cause spacetime to expand? If so, then there must be a coupling. If not, then these fields cannot expand with spacetime? Were they already present in infinity? Then the Big Bang only affects spacetime and no QM/QFT fields? If field fluctuations in the fields are to trigger something, then there must be a coupling. The only known coupling is GR. However, this is not supposed to have anything to do with quantum fields.

We can ask endless questions, but it always boils down to the fact that the fields of QM/QFT must have a coupling with spacetime. Otherwise, these fields would simply not trigger anything. I have never seen a description of this. This is a huge construction site in QM/QFT (not quantum gravity), but no one is working on it.

In DP, we have an easy job. All fields of QFT are low-dimensional spacetime configurations. Low-dimensional spacetimes only arise with the mapping of spacetime density from higher-dimensional spacetime. These fields did not exist before the Big Bang. Therefore, there cannot be any fluctuation in our case.

The limits of spacetime imply that geometric concepts such as size, length, etc. do not exist between 2D and 3D. Whether 3D spacetime expands is irrelevant to 2D spacetime. The coupling we know of are the particles of the Standard Model. This is the only possible mapping of spacetime density across the boundary. An electron shortly after the Big Bang, shortly before the speed of light, or on its way to the center of a black hole is always an identical electron. The electron does not care what drives higher-dimensional spacetime. It only has to be the mapping of a spacetime density.

In DP, the QM mapping for the Big Bang is not relevant for our 3D spacetime in the first step. However, the Big Bang is a 4D QM/QFT mapping in 3D. This is how spacetime is actually created. Our entire universe is probably just a 4D elementary particle.

The dimensional transition via spacetime density is the only coupling of the different spacetimes to each other.

Let’s move on to the fundamental question of cosmology. Why is the universe expanding, and what is actually expanding?

Don’t come at me with: “The Friedman equations from general relativity determine that there is a scale factor for space (not spacetime). This means that the universe must expand.” No, no, and no again. Mathematics describes nature. Mathematics is not a “force” of nature that can produce an effect. If such a statement is made based on a description, then there must be a physical reason for it. This is built into the mathematical model.

What is the reason? The answer in textbook physics is very simple: it is not known. Unfortunately, this answer is given too rarely. The mathematics of GR is always used as an argument. Dark energy is only there for later exponential growth. For the first billion years, let’s say, it played no role in the expansion. We need expansion immediately with and after inflation. Yes, exactly, we also need inflation so that the observations match. Then there is dark matter and dark energy, etc.

The observation of expansion and the scale factor from the Friedman equations fit together so nicely that the entire cosmology has been built on them. We already have the Big Bang, so the rest could be identical. We will show that the descriptions are almost identical from a certain point of view. However, we will use completely different foundations in DP.

For this reason, we will make a change in the structure of the text. Until now, we had first or simultaneously built up the classical view from the textbook together with DP. This makes the comparison easier. That no longer works here. We will first build up cosmology from the DP perspective. Later, we will compare this with the classical view. The approaches are too different. This means that the basis of cosmology from the DP perspective will seem a little strange to professionals in cosmology. Example: In the DP, spacetime changes and not just space. We will see that this is also the case with the Friedman equations. It is just very well hidden. For a complete picture of cosmology, Chapter 6 must therefore be worked through completely in the given order. The reference to textbook physics only comes at the end.

Let’s ask again: Why does spacetime expand? This question is very easy to answer in DP. Simply because of the existence of spacetime.

The chosen approach necessarily implies that spacetime can never be a static structure in itself. We do not need to search for the reason why. Conversely, without spacetime expansion or compression, the DP approach makes no sense.

If a spacetime point is a state of motion, it is not yet clear how the spacetime components must deform. So far, we have two deformations, one for spacetime density and one for spacetime curvature:

Let’s look at the available options to see if we can use them for expansion.

Scalar spacetime density sounds very good indeed. This is exactly what we are looking for expansion. But we have a problem. This scalar spacetime density for a mass-energy equivalent is defined by the fact that the energy is higher than in the surrounding area. This makes the time and space components shorter to the same extent. The definition of length becomes smaller. We need an enlargement, that is the observation. So, this is not so wrong. Only the direction is wrong. This means that expansion could be the counterpart. An enlargement of the definition of time and length.

But the next question immediately arises. If spacetime density must necessarily expand scalarly, why doesn’t a mass-energy equivalent do the same? In principle, there is no difference between an elementary particle and the entire spacetime in the Big Bang in terms of spacetime density. However, the elementary particle does not expand. We are very sure of that. Where is the difference? Fortunately, there is a spoilsport and an exception. In this section, we will only discuss the spoilsport. We will make the exception for redshift.

The spoilsport is QM. Every spacetime density from 3D onwards has a lower-dimensional representation. This representation knows no geometric information such as “size” beyond the dimensional boundary. The mathematical representation in QM is actually something like a point size when viewed in 3D. 3D spacetime is now no longer independent. It can no longer change the spacetime components as it pleases as long as QM has a fixed mapping. We absolutely need interaction so that the mappings of spacetime can be divided differently in QM. Without interaction, everything remains fixed. The mappings in 2D, with the particle zoo from the Standard Model, hold our spacetime together.

This is the same as above, except that the spacetime density is mapped to a specific spatial dimension (direction). The big difference is that the momentum is a mapping in 3D. This is explicitly not protected by the mapping in QM. We can see this behavior in neutrinos, for example. These particles are stable and were produced in large quantities in the early phase of the universe. Neutrinos are still measurable today. However, the momentum of these neutrinos has decreased due to expansion.

Here is another comment on motion. Momentum is explicitly a vectorial spacetime density. Only this can be perceived as motion in spacetime itself. In order for us to perceive a particle, we first need the scalar spacetime density. The motion of the particle is then the additional vectorial spacetime density. Therefore, expansion must be a scalar spacetime density. Nothing moves relative to spacetime, but only with spacetime.

The vectorial spacetime density is the inverse case of the scalar spacetime density for expansion. The inverse case of momentum is negative momentum. Is expansion then supposed to be deceleration? A loss of energy for spacetime? As you can see, it remains exciting. The resolution will come later in this chapter.

With spacetime curvature, the definition of length increases and the definition of time decreases. The greater length looks good at first glance. Why not gravity? The changes in the components of gravity are out of the question for two reasons.

Spacetime curvature is not a reaction of spacetime to itself. For spacetime curvature, we absolutely need different spacetime densities. Gravity reacts to this. If you like, spacetime curvature is a passive reaction. An imbalance must first be created, for example through QM. When directly mapping 4D to 3D, there is no reason to assume that spacetime was not completely homogeneous. 4D would not experience any fluctuation in 3D. Immediately after the Big Bang, the spacetime curvature in our spacetime should have been zero. Therefore, no expansion results from gravity.

We can rule out the second reason based on observations. Gravity is always directed toward a center and decreases with distance. According to observations, we need expansion that is nearly identical throughout the universe. This cannot be achieved with any interaction whose effect depends on range.

We would have arrived at a similar result if we had looked at the possible changes in the spacetime components in an overview. There are only time and space components. These can only increase and decrease. The number of possible combinations is small. We expand the first overview of the deformations:

Deformation

Deformation

Spacetime curvature/gravity

Spacetime density

Anti-gravity

Expansion

We have the known deformations. However, there may also be a counterpart to each of these. In physics, the counterpart is often referred to as “anti.” Therefore, we refer to the counterpart to gravity as anti-gravity and the counterpart to spacetime density as expansion. Please do not refer to it as anti-spacetime density.

We do not allow certain types of combinations. If there is a change in a space component, then there is also a change in the time component and vice versa. We do not allow the possibility of a change in the space component without a change in the time component or vice versa. A change in the definition of length is always a step toward or away from the spacetime boundary. Since time is the measure of distance to the spacetime boundary, within DP, a change in space and time always works together. If we have learned anything from SR and GR, it is that spacetime should be regarded as a single substance. The components change together with equal intensity or not at all. An expansion that only involves space but not time is not possible for us. This once again puts us at odds with the current doctrine on expansion. The resolution comes later and is surprisingly simple.

What we can easily see in the above list is that gravity is not the counterpart to expansion. This is often explained incorrectly. Gravity only ensures the continuum in spacetime. Gravity does not care about expansion or contraction. It only reacts to fluctuations in spacetime density. However, it does not explicitly change the spacetime density. If spacetime density changes homogeneously without fluctuation, there is no gravity or anti-gravity.

This makes it clear what increases during expansion. The definition of length and time becomes larger. Even during expansion, there is no squeezing or pulling. At every point in spacetime, the definition of length and time is enlarged. This leads to greater distances. We cannot detect the change in the definition of time because it does not add up over a distance. We will do this at the end when we compare it with textbook physics.

Wait a minute. If this happens identically everywhere in the universe, then I wouldn’t be able to detect this increase. Almost correct. However, the elementary particles that make up everything do not participate in this. QM does not allow this. This means that spacetime becomes larger and larger in relation to an object. In addition, we measure this from a gravitational field. Gravity is not the counterpart, but it does resist expansion. Expansion wants a larger definition of time, gravity a smaller one. QM and gravity increase the resistance to expansion.

We now have all the pieces together to describe the process of expansion. In doing so, we will find that a form of matter must explicitly form, namely dark matter. These only forms when spacetime behaves in a certain way, namely inflation. Since dark matter is created, inflation in DP looks different than in textbook physics.

We have already covered this. A 4D spacetime density is mapped onto our spacetime. This creates our spacetime. The spacetime density is completely homogeneous. The mapping is below the dimensional constant, otherwise a black hole would form. We have already made an estimate of the size. This means that spacetime still starts with an extremely high spacetime density. Then spacetime expansion begins. QM actually needs some time. This means that expansion starts before QM.

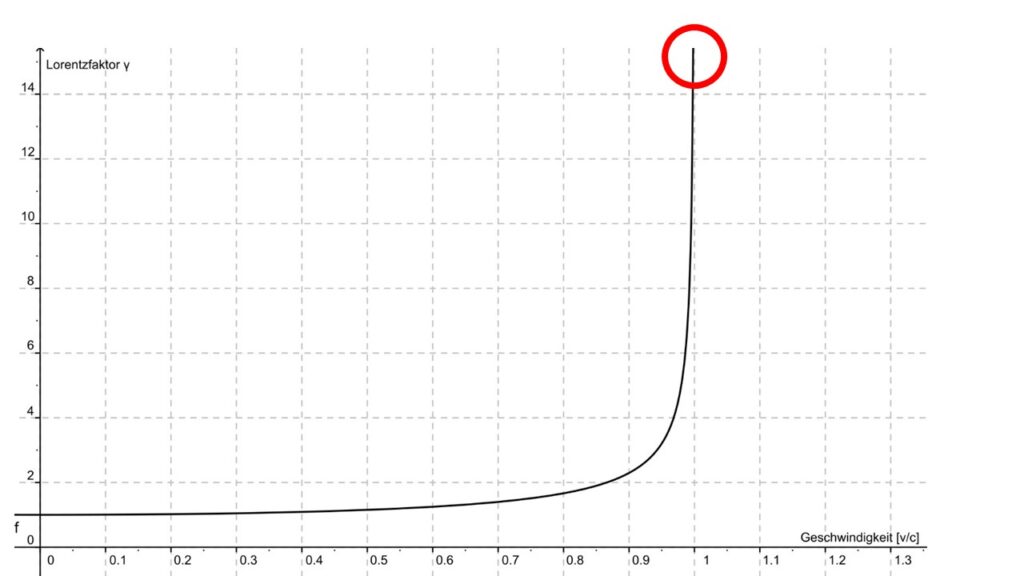

In DP, inflation is a necessary prerequisite for the start of expansion. There is no additional field, there is no fluctuation, there is no symmetry break, there is no … (think of any name you like, it has certainly been used before). Nevertheless, there is exponential growth in the definition of length. The solution is very simple. Let’s take a look at the graph.

This is the illustration of length contraction and time dilation (Lorentz factor) from SR. The solution must already be contained within SR in DP. Gravity is only the compensation for a fluctuation in spacetime density. We don’t have that at the Big Bang. So, the reason for the expansion must already be contained in SR. We just have to reverse the direction. We need time relaxation and length relaxation. The Big Bang is the starting point. That is the red circle. Somewhere far above. Whether a 3D spacetime starts with an inflation phase depends solely on the amount of spacetime density represented by 4D.

We do not need any further “vacuum conditions” for inflation to stop again. Everything happens automatically here. The entire process of inflation is already contained in SR. However, inflation itself is a different process here than in textbook physics. Contrary to textbook physics, we do not need inflation at all to solve certain problems. Flatness of spacetime, horizon problem, etc. We do not have these problems at all with the initial condition of homogeneous spacetime density. Nevertheless, inflation is still there and cannot be avoided in a 3D spacetime with so much spacetime density.

Something unexpected happens during inflation. Black holes are created. Not just any black holes, but the smallest possible black holes. But let’s take it one step at a time.

Spacetime expands. This causes an energy change in spacetime. Spacetime “thins out.” According to our logic, this means less energy. Nothing changes for spacetime itself. A meter remains a meter because the definition changes. It follows that there is no local change in energy for spacetime. The energy simply has to be distributed over a larger volume. The content thins out, but the total amount does not change. Thus, the DP implies energy conservation for the entire spacetime with expansion. The spacetime density only transforms.

Due to QM, an elementary particle will not participate in the extreme dilution during the inflation phase. Then the energy of the particle will increase exponentially. This is like the equivalence principle. No interaction from outside, but still a change. In the case of gravity, this is due to the opposite deformation of space and time. Thus, without an change in the energy conditions. Here, however, space and time become uniformly larger. The elementary particle gains energy because the valence of the spacetime density of the elementary particle changes in relation to its environment. We have called this a potential field. Here, directly for energy.

Spacetime is a potential field for energy.

This means that every elementary particle in the inflation phase that does not decay quickly enough receives an exponential increase in energy. However, this only goes up to the dimensional constant. Then a black hole forms, with the exact Planck mass. This gives us the smallest possible black hole that can form in our spacetime. Once the exponential growth of the length definition is over, this can no longer happen.

If spacetime is a potential field, black holes must necessarily form from the first stable elementary particles in combination with inflation. The inflation phase does not last very long. The reason is simple but also surprising. With length contraction and time dilation, there is a maximum speed, the speed of light. Space and time dimensions cannot go below zero. In the opposite direction, there is no maximum limit. Expansion is very rapid at the beginning. Only the onset of quantum mechanics and gravity slows it down.

These smallest black holes have a very special property. Their cross-section is close to zero. A quick calculation shows that a black hole with Planck mass has a Schwarzschild radius of 2 Planck lengths. That is incredibly small. It is so small that absolutely no particle from the Standard Model can fit into the black hole in one piece. If such a black hole wants to consume something, it must be able to take in an elementary particle as a quantum (in one piece).

These are black hole corpses. They cannot do anything with matter. This means that black holes remain what they are from the moment they are created. These black holes therefore have the following properties:

This means that these black holes in DP are dark matter. Again, there are no new elementary particles or fields. The formation of dark matter is a necessary part of the process.

Due to their tiny cross-section, these black holes would not merge even in the early universe. However, black holes will behave like elementary particles and gain mass during the inflation phase. These objects are stable and will gain ever greater mass as spacetime density “thins out”. The black holes must first form and can then grow. Therefore, not all black holes will undergo a large increase in mass. This means that we will probably have black holes in the universe even before the first molecules. And then there will also be some with greater mass. It should therefore come as no surprise if a JWST finds more and larger black holes than the standard model of cosmology or the growth limit of general relativity (Eddington limit) allows. We don’t have to wait for star formation and collapse.

This means we have found our estimation error in the mass of black holes. They do not have to derive their mass solely from the accumulation of matter. Black holes also grow with the expansion of spacetime. Very strongly until the kink in the diagram, then less and less. In addition, gravity increases at the black hole and creates resistance to expansion. The calculation for this is therefore not simply linear. It is somewhat more complicated.

Based on the DP, the JWST must find many large black holes in the early universe that cannot be explained by standard models.

As can be seen in the diagram, inflation does not stop abruptly but weakens with a “kink.” Not linearly slowly. However, this has the effect that the elementary particles have a smaller momentum at this time than is assumed in the standard model. The dilution of spacetime to the spacetime density of a particle can also be seen in the momentum. However, momentum is the “antagonist” of gravity. The statement that momentum from an interaction in an early universe is no longer as valuable follows in exactly the same direction. Gravity can capture elementary particles more easily. Individual objects, such as stars, may be larger than predicted during this phase. Once an object has generated a large gravitational effect, the effect weakens as gravity again exerts greater resistance to expansion. Unfortunately, this again leads to the conclusion that it is not possible to simply calculate this back linearly. It is much more complicated than that.

The long straight line after the kink is the most boring part of the development. Don’t forget to read the diagram from right to left. Everything here proceeds as described in the textbook. The last 13 billion years or so of spacetime lie almost entirely on this straight line. Inflation and the kink have an enormous impact but are the smallest part in terms of time. From the straight line onwards, the expansion rate can be considered almost constant.

Based on this progression, the expansion should continue to decrease from the past toward the future. Observations show the opposite. The culprit is easy to find. If it is not spacetime itself, then it is QM. In textbook physics, attempts are made to identify the vacuum through quantum fluctuations as the driver of expansion. In our case, QM does exactly the opposite. It prevents spacetime density from expanding. In our case, the vacuum is also a spacetime density and therefore has energy. This must also be reflected in QM. This results in quantum fluctuations in the vacuum. No negative energy needs to be borrowed for pair formation. Spacetime corresponds to energy. This means that energy is always present.

This means that we have several factors responsible for expansion. Expansion should simply slow down due to the behavior of spacetime itself. As the universe clumps together due to gravity, expansion encounters ever greater resistance. So, expansion must decrease after all. However, the energy density and thus the “braking power” of the QM is also decreasing. Here, too, we cannot simply calculate expansion linearly. Unfortunately, that is too simplistic. The universe should have a different Hubble constant in the different phases of its development.

What we do not have is dark energy. This is not needed in DP. Spacetime itself is the driver of expansion. This is why the cosmological constant Λ in Einstein’s field equation makes sense. It is simply a scalar value for the metric. This value must be greater than zero; we are expanding. However, this value is not constant. It corresponds to the curve in the diagram and must become smaller and smaller. We will come back to this in a moment. However, due to the many factors involved, the expansion does not proceed as evenly as shown in this diagram.

The expansion is mainly measured via the redshift of photons. According to our logic, this should not be possible. QM prevents an expansion of spacetime density. I have described QM as a spoilsport. I have also already mentioned that there is one exception. The exception is the photon. If this exception did not exist, we would not be able to observe an expanding universe.

The photon has no rest mass and therefore cannot explicitly have a QM representation as a black hole. A photon is an extrinsic manifestation of a 2D spacetime in 3D. In 2D itself, there is no manifestation. If we remain in the wave picture of the photon, then the wavelength is given in 3D and not in 2D. This results in higher spacetime density in 3D and cannot be captured by QM.

Therefore, redshift, as an increase in wavelength, is directly the spacetime expansion. This redshift is not an effect of objects moving apart. It is 1 to 1 expansion. This also makes sense, since a photon that was created 13 billion years ago could not have known about the existence of Earth or a telescope. This cannot be purely relativistic due to observers.

We urgently need to address the mathematics of GR here. Until now, we have used the field equation in this form:

G_{\mu\nu}\space =\space k\space *\space T_{\mu\nu}

The Einstein tensor indicates the curvature of space, and the stress-energy tensor indicates the source. The stress-energy tensor is the collection of all different mass-energy equivalents. However, part of the collection of mass-energy equivalents is missing. More precisely, the largest part of the energy in the universe. Spacetime itself, the vacuum. In a vacuum, the stress-energy tensor is zero. However, this does not correspond to our understanding. Every point in spacetime has an energy greater than zero. This means that we have to incorporate an evenly distributed quantity into the equation for the vacuum. Mathematically, the simplest solution is a constant for the metric. In fact, this is one of the few changes to the field equation that does not destroy the structure behind it.

We must use the field equation with the cosmological constant. The formula then looks like this:

G_{\mu\nu}\space =\space k\space *\space T_{\mu\nu}\space -\space \Lambda g_{\mu\nu}

I write the cosmological constant on the side of the stress-energy tensor, as this is an energy contribution. The cosmological constant is simply a scaling factor on the spacetime metric. This fits with our explanation. Spacetime undergoes length and time relaxation to the same extent. This is simply a constant number. However, the number \Lambda is not constant. It must follow the curve from the diagram above. The sign must be different from the stress-energy tensor. This part of the energy produces a “negative” energy contribution. A larger spacetime density is a plus and a smaller one is a minus. Therefore, we need a positive constant. A \Lambda smaller than zero would counteract our logic. In the QM representation in 2D, we therefore need an anti-de-Sitter spacetime. This must counteract the cosmological constant. In fact, according to GR, a black hole in 2D is only possible in static anti-de-Sitter spacetime.

There are many more aspects to cosmology than those listed in this chapter. However, we have to draw the line somewhere. As the final part on cosmology and also part 2, we want to compare the views of DP and textbook physics.

Here, we will only discuss a comparison of the view from the Friedman equations to DP. Anything else would result in a very long text. We will see that there are actually only very minor differences. We need to get to the bottom of the question and assumption behind the Friedman equation. Then we get something similar to SR. Although the spacetime density does not appear to be compatible with SR, we get the same results.

The first step toward the Friedmann equations is the assumption that the universe is homogeneous and isotropic. Observations of our immediate surroundings, e.g., our home galaxy, suggest the opposite. Hence the assumption that this is valid for large scales in the universe. This assumption does not hold true. There is no clumping in the universe. According to the stress-energy tensor, the mass distribution in the Friedmann equation is completely homogeneous, without any graininess. This brings us to two points.

These two points have several implications.

Homogeneous and isotropic are entered into the signature as 100% homogeneous and isotropic. This means that there are no distinguishable mass-energy equivalents in this approach. The universe is regarded as a single large mass-energy equivalent. No “granularity,” no matter how fine or course, is intended. Thus, the mass density c^2\rho in the 00 element of the stress-energy tensor is a true continuum. This is a very good description of energy density. Full agreement.

Since the energy density in the 00 element cannot fluctuate, there can be no gravity from the DP perspective. In textbook physics, the reaction to energy density is also considered to be gravity. But then a repulsive one. We do not classify this as gravity, but as expansion. The deformations of the spacetime components are different. Except for the naming, however, there is also agreement.

The big sticking point is the pressure p on the 11, 22, and 33 elements. Here’s a simple question about this. Where does this pressure come from? The textbook has a simple answer: thermodynamics. There are particles in the universe that interact, and this creates pressure. In principle, it is assumed that the energy density of mass distribution corresponds to that of dust. The individual particles then participate in thermodynamics. The mass distribution behaves like a liquid. There is always pressure within it. The entire assumption for the pressure is based on the fact that mass is present in point-like particles. We don’t know it any other way. These particles have momentum and thus generate pressure. Pressure on what? Does mass with momentum generate pressure on spacetime? Then we are back to the discussion of coupling to spacetime. If we assume individual particles, then this would also have to be included in the energy density. But this is a pure continuum. The pressure does not match the energy distribution.

This means that two assumptions are included in the stress-energy tensor: a homogeneous and isotropic distribution of energy density and pressure exerted by the particles on themselves. The granularity for the pressure is not included in the energy density. The pressure is exerted on the 11, 22, and 33 elements. This is not pressure like momentum in a specific direction. I would consider this a self-fulfilling prophecy. We put in “scalar” pressure and get “scalar” response from spacetime.

In DP, this pressure results from length and time relaxation. This is a “negative” energy for energy distribution. The signs of energy density and pressure must be different. According to the deformations of the spacetime components, these are the counterparts of each other. The cosmological constant is the behavior of the metric. The pressure is the appropriate energy specification for this.

We can therefore conclude that DP enables the assumptions of the Friedman equations better and more easily than textbook physics can.

There is another major difference to discuss here. The Friedman equations give us a scale factor for space, not for spacetime. In the DP, however, we always assume a change in spacetime. Space as an independent object no longer exists there. What is the difference here? The simple answer is that there is no difference.

In the Friedman equation, the time component also changes. This can best be seen when the stress-energy tensor with the signature is inserted into the equation. For the 00 or, better, tt component of the stress-energy tensor, we obtain a term in the Einstein tensor. It looks like this:

\cfrac{\dot{R^2}}{R^2}\space +\space \cfrac{k}{R^2}\space =\space \cfrac{8\space *\space \pi\space *\space G}{3}\rho

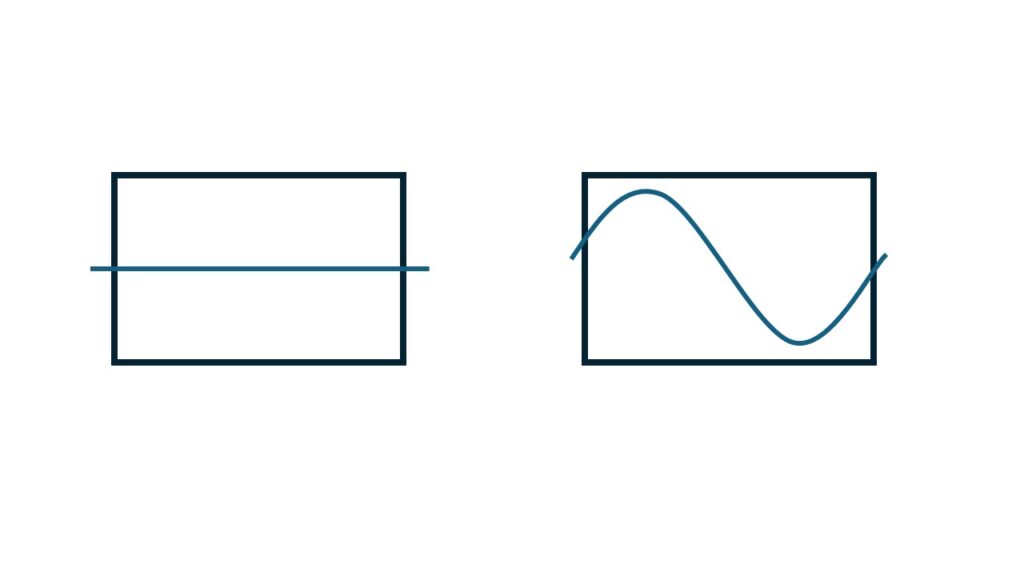

The time component has an active effect. The problem with this is that we cannot recognize the effect on time in the given question and assumption of a homogeneous and isotropic universe. Consider the following image:

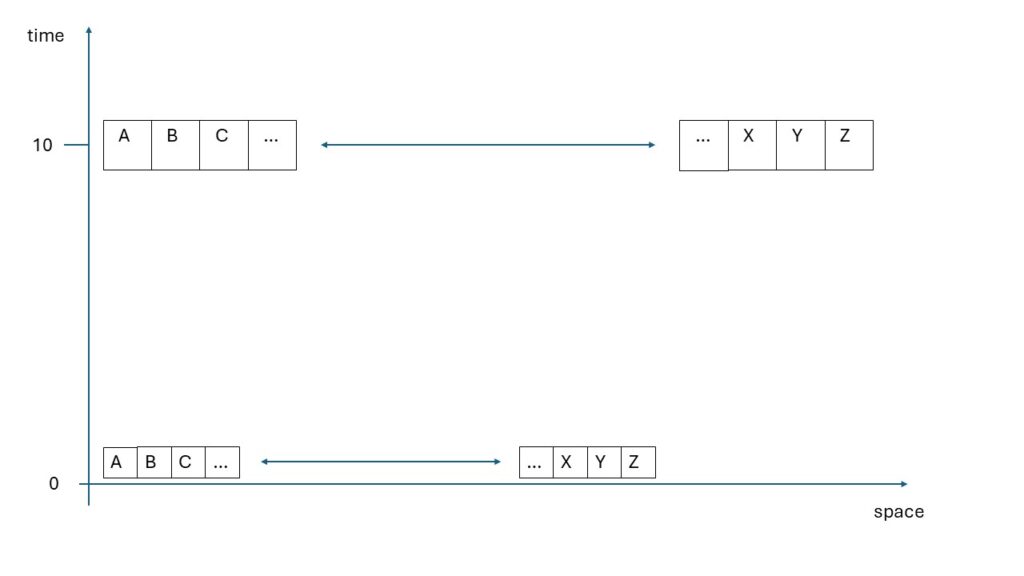

We are at point A and measure the distance to point Z. The rest of the alphabet is represented as points along the route. At time t = 0, we have a fixed distance R between A and Z. We take another measurement at t = 10. As a function R(10), since the distance must depend on time.

Each letter on the distance has now become x larger. This applies equally to every letter, as we are assuming a continuum. If we now want to determine the distance, the change over the distance is added up. The further away the letter is, the greater the distance has become. We see this in the expansion of the universe.

Due to the continuum, time also speeds up for each letter on the line. Time relaxation is a faster passage of time. This means that the passage of time is identical in each letter. There is no difference in the passage of time from one letter to the next. The crucial thing, however, is that we want to query the new distance at R(10) at point A. The change has already been incorporated into the time parameter 10. These are no longer the identical 10 seconds as at t = 0. However, we cannot determine this. The definition of time has changed. 10 time units are 10 time units for every letter on the route.

The route change adds up in time. The time change is already included in the question and is not added. Of course, spacetime is always adjusted in the Friedmann equation. But we cannot determine this. The assumptions and the question specify that there must be no time relaxation from this equation. Otherwise, we would be counting the time relaxation twice. The funny thing is that we would otherwise refute a basic assumption of SR, namely that there is no simultaneity.

For the DP, the Timescape model represents a very good test of cosmology. This model does not assume a homogeneous universe. Since there are areas with high gravity, e.g., galaxy clusters, and areas with weaker gravity, e.g., voids, different perspectives are created for the escape velocity of objects. This means that dark energy is not needed here. The difference here comes only from the difference in gravity and thus from time dilation. However, the effect may be too weak to explain the ever-increasing expansion.

According to DP, this effect must be greater. The reason is that spacetime is expanding in our universe. This further amplifies the difference in time dilation. What I believe is not taken into account enough is that we make measurements of supernovae, always from our high gravitational potential (from a galaxy) to another massive object (a large star, presumably also in a galaxy). Over a long distance (billions of light years), this does not correspond to reality at all.

We agree with the Timescape model and claim that the effects must be stronger.

That was a lot of work to get this far. The basic idea behind DP and how it can be applied in physics should now be clear. Certainly not all questions about DP or its interaction with SRT and ART have been answered. If you still have questions, please use the contact form.

However, we still have a long way to go: Part 3, QM. The first version of this part is currently available for 2026. I am continuing to work on it. Since QM is quite a bit more complicated than GR, it will take some time. I do not want to provide the QM from an old version, as some things have changed and are no longer correct in the old version. Enter the text “Subscription” in the contact form. You will then receive an email when I have finished a new part. This will probably happen in another 3 updates.