Everything consists of spacetime.

The first steps in the development of DP were based on several different starting points. None of these was the approach we will be building on here. Over time, the various approaches converged on this point. That was the moment when a theory was formed from a collection of loose ideas.

The basic idea is the continuation of an ingenious thought by Einstein. In addition, this idea is taken to an absolute extreme. If gravity is represented as a purely geometric description in spacetime (spacetime curvature), then we must “simply” apply this idea to everything else.

Then everything is a geometric representation in a single object, spacetime.

How did we come up with such a bizarre and extreme idea of wanting to map everything onto a single object? What we want to achieve is the unification of GR and QM. However, this task is proving to be a very tough nut to crack. The brightest minds have been trying to do this for over 100 years and have not yet found a truly valid solution. More voices are saying that this may not even be possible. In fact, the idea of unification is only a wish of physicists. No one can say with certainty whether it is even possible. Therefore, the steps towards unification are becoming smaller. Very specific properties of possible unification are being investigated. Our approach is the exact opposite of this.

We assume that unification is fundamentally possible and select the most extreme form from the possibilities. Those who embark on the search for the Holy Grail do not question its existence. But the question arises: Is there any indication that the approach of “everything is an object with a geometric mapping” makes any sense at all? Well, if I ask the question.

To do this, we start in the physics kindergarten and first look at a small and well-known formula.

r_{S}\space =\space \cfrac{2\space *\space G\space *\space M}{c^2}

With this formula, we can calculate the Schwarzschild radius of a mass. The black hole of the mass has no charge and does not rotate. This representation of the equation is very consistent with our intuition.

r_{S}\space =\space \cfrac{2\space *\space 6.6743 *\space 10^{-11}\space * \space 6\space *\space 10^{24}}{299792548^2}

For the Earth, we arrive at approximately 9 mm. I have simply omitted the units of measurement. The result is a length. Everything is kept very simple. This is an equation and therefore an identity. There must also be a length on the right-hand side. We don’t recognize this at first glance because the individual components are not lengths. This means that although the gravitational constant, the mass, and the speed of light on the right-hand side are not lengths, we can combine them to form a length. Now for the physics kindergarten. Why are we allowed to do this? These are very different objects and none of them are lengths. We don’t think about it for long. If the units of measurement are identical, we can compare both sides. Therefore, we can also describe the Schwarzschild radius with other objects. We “only” must obtain a length with the identical result.

Therefore, we have chosen a rather unusual representation.

r_{S}\space =\space \cfrac{2\space *\space l_P^2}{\lambda_C}

l_P refers to a Planck length and \lambda_C refers to a Compton wavelength. Here we need the Compton wavelength of the Earth. If anyone wants to check this calculation, I always leave all Planck units and h unreduced (not divided by 2\space *\space \pi). For the Compton wavelength, we assume a scattering angle of 90 degrees so that the cosine drops out of the formula. This gives us:

r_{S}\space =\space \cfrac{2\space *\space 1.6413\space *\space 10^{-69}}{3.6837\space *\space 10^{-67}}

We get our approx. 9 mm again. This time we only used lengths. Seems much more “natural.” However, the lengths used are the Planck length and the Compton wavelength. These are objects from QM and not from GR. It works anyway. With this different representation, we obtain additional information.

Example: We know that there cannot be a Compton wavelength smaller than the Planck length. Otherwise, the energy would have to lead directly to a black hole during scattering. If we enter l_P instead of \lambda_C

in the above formula, the lower limit is a Schwarzschild radius of two Planck lengths. This appears to be a lower limit for a Schwarzschild radius. We cannot see this relationship from the first representation. The fact that we can choose different representations is therefore very useful for us.

We can choose another representation. Here, M_E is the mass of the Earth and m_P is the Planck mass.

r_S\space =\space 2\space *\space l_P\space *\space \cfrac{M_E}{m_P}

r_S\space =\space 2\space *\space 4.0513\space *\space 10^{-35}\space *\space \cfrac{6\space *\space 10^{24}}{5.4555\space *\space 10^{-8}}

We again obtain our approx. 9 mm. In this representation, it appears that the Schwarzschild radius is only twice the Planck length (i.e., the smallest possible value), which is changed by a factor of a mass ratio. Since the Schwarzschild radius cannot be smaller than two Planck lengths, a mass smaller than the Planck mass cannot form a black hole. Again, new information. Somehow, we can always arrive at a representation with length and mass. We can rearrange the last formula slightly and obtain:

\cfrac{r_S}{l_P}\space =\space \cfrac{2\space *\space M_E}{m_P}

Now it is a length ratio to a mass ratio without a unit of measurement in comparison. It seems that representations in our spacetime, such as a Schwarzschild radius or a mass, must adhere to certain limits.

Let’s take a second well-known example. But now we’ll start with a formula for specifying a ratio. In other words, a result without a unit of measurement.

F_{Elect}\space =\space \cfrac{e^2}{4\space *\space \pi\space *\space \epsilon_0\space *\space r^2}

F_{Grav}\space =\space \cfrac{G\space *\space m_1\space *\space m_2}{r^2}

The first formula is the classic description of static electric force. The second formula is the classic description of gravity as a force. Presumably, no one will have a problem with the next steps. We substitute the mass of an electron for m_1 and m_2 and the elementary charge of the electron for the charge e. Then we put the two equations in relation to each other, because both equations have the same unit of measurement.

\cfrac{F_{Elekt}}{F_{Grav}}\space =\space \cfrac{\cfrac{e^2}{4\space *\space \pi\space *\space \epsilon_0\space *\space r^2}}{\cfrac{G\space *\space m_1\space *\space m_2}{r^2}}

r^2 cancels out, and then we plug in the numbers. This gives us:

\cfrac{e^2}{4\space *\space \pi\space *\space \epsilon_0\space *\space G\space *\space m_e^2 }\space =\space 4\space *\space 10^{42}

This is an extremely large number. This means that the difference between the forces of gravity and the electric field is a number with 42 zeros. We can check this with a rough estimate. Take a small, weak refrigerator magnet and use it to lift a metal paper clip. The result is that the magnet exerts a stronger electric force than the entire Earth with its gravity. The result is correct and accepted by all physicists. If you have seen a different, and in any case smaller, number, this is not a problem. It depends on which particle is used for the mass. We take the electron, as this is the smallest particle with a charge in terms of mass. We will need the calculated number with the electron again later.

Here, we have compared gravity as a force and the electric field as a force. However, these fundamental forces should not be compatible. Many objections may now arise. It is only old classical physics, gravity is not a force, no example from quantum mechanics, etc. All objections are correct. The principle of the first example applies: if the units of measurement match, we can compare the mathematical expressions. The principle applies to all units of measurement, and there are many of them. It does not matter where the description as a formula came from. If we manage to make the units of measurement match, we can compare them.

Here we can again choose an unusual representation. With \alpha as the fine structure constant.

\cfrac{F_{Elect}}{F_{Grav}}\space =\space \cfrac{1}{2\space *\space \pi}\space *\space \alpha\space *\space \bigg(\cfrac{m_P}{m_e}\bigg)^2\space \iff\space \cfrac{F_{Elect}\space *\space 2\space *\space \pi}{F_{Grac}\space *\space \alpha}\space =\space \bigg(\cfrac{m_P}{m_e}\bigg)^2

None of the individual terms has a unit of measurement, and yet everything fits together. A force ratio, with a correction factor for each force, is nothing more than a mass ratio squared. If you remember the first formula, we could also use the square of the Schwarzschild radii. It appears that we can choose almost any representation for the identical statement here.

We will try to formulate our findings from the two examples into a new idea. In physics, there is only one object, and the unit of measurement is only a certain view of this object. We look at the identical object and put on different glasses. Then it is logical that if we can compare terms that we have converted to identical units of measurement. It is all the same.

When unifying GR and QM, these units of measurement are very different. In GR, there is a length in the curvature of spacetime. In QM, there is a probability. But a probability is not a unit of measurement at all. These are very different pairs of glasses. This is where the problem and the solution lie. Although we start with the idea of a single object, we will find that QM considers something completely different from GR. Therefore, there will be no unification as a mathematically identical description. On a logical level, both theories are integrated into a comprehensive unified framework, Dimensional Physics.

We need to set some kind of “anchor” as a starting point. We don’t want to create a completely new description, like string theory. We want to combine the descriptions given of GR and QM. The idea is to work with only one single object. In fact, with GR, the first half is already done. Therefore, contrary to the entire mainstream in physics, we start with GR. Since we started from GR, we take the characteristic equation for GR in its simplest form: Einstein’s field equations.

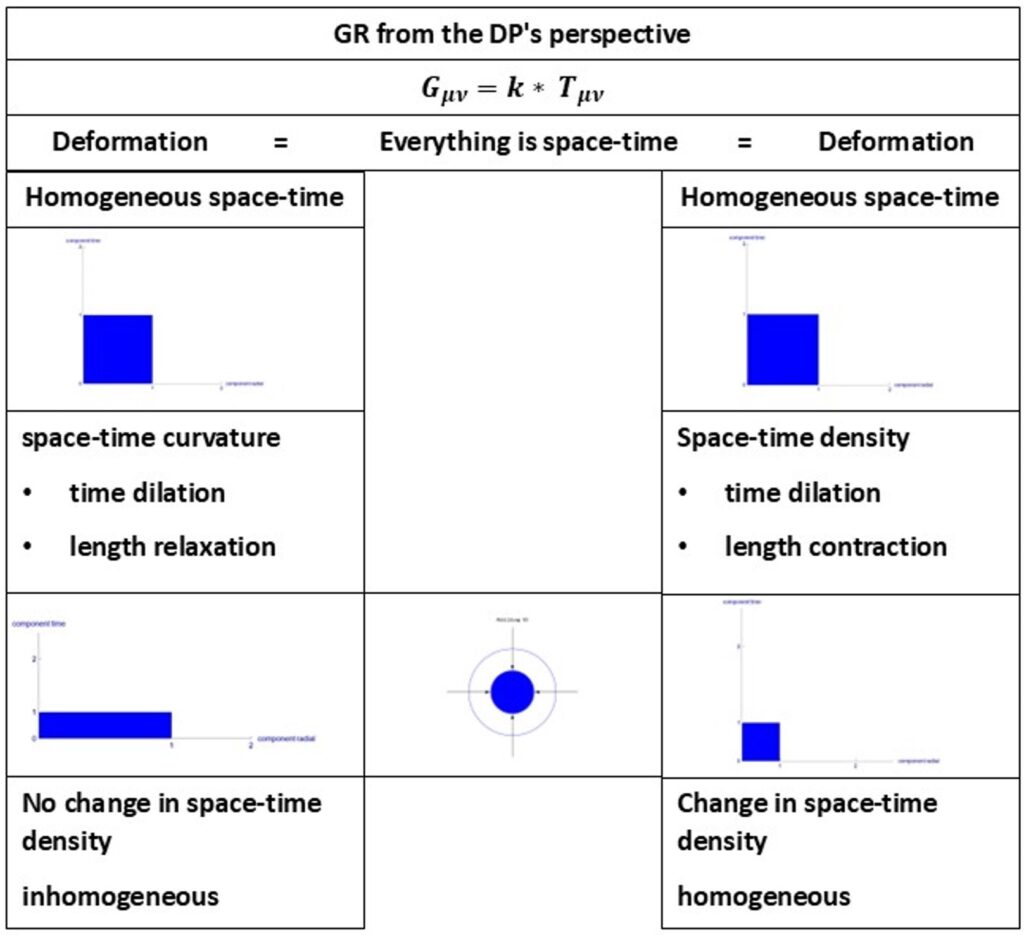

G_{\mu\nu}\space =\space k\space *\space T_{\mu\nu}

Let’s take a closer look at the structure of the equation.

The first thing that stands out: Why field equations? There is only one equation. This notation is very compact. There are 16 individual equations that together form a system of equations. The Greek letters μ and ν count from 0 to 3 (this is the convention). Each letter stands for the number of dimensions in our spacetime. Textbooks count 4 dimensions for our spacetime. Three spatial dimensions and one temporal dimension. In fact, there are 4 spatial dimensions in the equation. The temporal dimension is given an additional factor, which turns time into a length. In the mathematical description, the unit of measurement for the temporal dimension is a length and not time. The time dimension is given a different sign than the spatial dimensions. Spatial dimensions are given a plus sign, and the time dimension is a minus sign, or vice versa. How this is done is purely a matter of opinion. The important thing is that the signs are different. This is called the signature of spacetime. We use the signature (- + + +).

The capital letters are tensors. They describe how the content of the tensors behaves from one dimension to another. This results in 4 * 4 possibilities = 16 equations. However, due to symmetries, we only need 10 independent equations.

Contrary to the textbook, we will only count the real spatial dimensions, i.e., those with +. This makes our spacetime 3D. Why we do this is explained in Chapter 3, “Limits of Spacetime.” The additional time dimension results automatically for any spacetime configuration. We will see that this signature alone is not sufficient for classifying spacetime.

The left side of the equation only has the tensor with the designation G, the Einstein tensor. This describes, let’s call it very generally, a deformation of spacetime itself. This type of deformation is called spacetime curvature. In GR, spacetime curvature is equated with gravity. Thus, gravity is not a force or interaction, but a geometric mapping onto a single object, spacetime. Our approach is to obtain a geometric identity across all considerations onto one object. This already achieves the desired form of description for gravity. This immediately raises the question of whether we can achieve the same for the other side of the equation.

We transfer the idea of a mapping in spacetime to the other side of the equation. There we have two elements. First, the small k. This is a proportionality constant. It contains only fixed values and thus, in a mathematical sense, represents only a fixed number with the appropriate unit of measurement. We will examine this k later. Then there is the stress-energy tensor T. This contains everything that is referred to as mass-energy equivalent. As with G, it is divided between the respective dimensions.

Without even noticing, we have already achieved our goal. Yet it looks like the opposite. The stress-energy tensor is a wild collection of everything the universe has to offer without gravity. How can an equation with such a collection of vastly different objects be represented so clearly? Because the collection is not as wild as it looks. Let’s close our eyes, and I mean all mathematical eyes, and look at the equation as a union of GR and QM. G describes gravity and T collects the entire particle zoo from the Standard Model, plus momentum, charges, etc. We know that the descriptions do not match, and yet we still have an equal sign here. For this equation to work and for the difference to QM to arise, GR must adopt a special view of this collection of mass-energy equivalents. The differences must be normalized or, to put it bluntly, the right side must put on the right glasses. As is so often the case in physics, this is done via energy. No matter how different the contributions from the stress-energy tensor are, GR must adopt a normalized perspective. GR may only be interested in two things from T: the amount of energy and the possible alignment with the dimensions. Any “internal structure” of a mass-energy equivalent (whether it is an electron, photon, proton, etc.) must be ignored.

This is an equation. Therefore, the units of measurement are identical on both sides. The Einstein tensor only uses spacetime with deformation. The unit of measurement is a specification of length. We do the same with the stress-energy tensor. A geometric mapping in spacetime with the unit of measurement being length. Certain requirements are placed on this geometric mapping in the stress-energy tensor. The equation must continue to work, and all statements of general relativity about gravity must follow from it. For some of the statements, the mapping must already match quantum mechanics at this level. That sounds like a very difficult geometric mapping in spacetime. The opposite is true. We will assume an evenly distributed “density” of spacetime itself in a specific spacetime volume.

The deformation of spacetime for gravity is called spacetime curvature. Then we also need a name for the deformation on the other side of the equation. Therefore, by sovereign arbitrariness => the deformation of spacetime for a mass-energy equivalent is called: spacetime density. The term “density” describes this deformation very well in certain places, but in other places it is rather misleading. The name density is intuitively based on everyday experience. The density of spacetime is defined differently from the density of any substance. However, we must give it some name. So, we will stick with spacetime density as the source of spacetime curvature.

We only need four assumptions to provide a complete description of physics:

We will see that the conclusions drawn from these assumptions will lead us to the description of physics that we are familiar with. If someone had told me this before the DP was developed, I would have thought they were crazy. However, this approach has a major advantage for testing the DP. There is almost no choice in the conclusions. Either the logic is correct, or the entire theory collapses. There are very few places where there is still room for “extensions.” The possibilities found in other theories, with smaller structures, higher energies, higher masses, additional particles, symmetry breaking, etc., do not exist here.

We could even derive spacetime as a substance, with the properties of continuity and differentiability, from the assumption of spacetime density. We will leave our approach divided into these four points. This is better for understanding. Thus, the only real additional assumption to known physics is spacetime density. What could really change? Almost everything, without really having to adjust the mathematics. As I said, it sounds a bit crazy.

We have introduced spacetime density into the world. Then we should do two things first:

Let’s not make life more difficult than it is and start with something familiar. Spacetime curvature has been known for over 100 years and is well understood mathematically. Spacetime density is the source of spacetime curvature. We can therefore see spacetime curvature as the reaction of spacetime to spacetime density. This behavior is described by the field equations. The definition of spacetime density must be consistent with the existing solutions to the field equations.

In this text, we always use Schwarzschild’s solution to the field equations. This has advantages but also disadvantages. The big advantage is that this solution is the simplest. Schwarzschild found this solution only a few months after Einstein’s publication. It is a vacuum solution for non-rotating masses. We are sure that this is a strong simplification. However, it is sufficient for our purposes.

In order to understand the solution, we need to write down the signature of spacetime (- + + +) in full. The signature is simply a shorthand form of a metric. The metric of spacetime defines the behavior of spacetime in relation to the field equations. In a sense, the metric is the solution to the equation. 4 x 4 entries for all the different divisions between the dimensions. Equally important for us: Metric is the appropriate definition of geometry for spacetime. Schwarzschild metric:

\begin{pmatrix} -c^2(1\space -\space \cfrac{r_S}{r} )dt^2 & 0 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & +\space \cfrac{1}{(1\space -\space \cfrac{r_S}{r})}dr^2 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & +\space r^2d\theta^2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & +\space r^2sin^2(\theta)d\phi^2 \end{pmatrix}

Don’t panic, it looks worse than it is. In the diagonal of this matrix, you first see the signs from the signature (- + + +). Behind them, however, there is a term in each case. The last two terms with θ or φ are not relevant for us at the moment. This solution is based on spherical coordinates. The last two entries indicate the position on a spherical surface. Like the longitude and latitude on the Earth’s surface. However, we are only interested in the distance, i.e., the radius of this spherical surface, and not the position on it. Fortunately, in the case of gravity, the effect only depends on the distance. This means that only the first two terms are of interest.

The first term is the time dimension. This can be seen from the dt^2 and the minus sign. However, this term is multiplied by a c^2. Speed is a length divided by time, and the time dimension is only a time. After simplification, only a length remains. In mathematical terms, the time dimension is converted into a spatial dimension. There are 4 spatial dimensions. We will stick to the terminology used in textbooks and still refer to it as the time dimension. The small r is the distance from the gravitational source and the r_S is the Schwarzschild radius. The event horizon of the black hole.

The second term is the radial distance to the gravitational source. You don’t have to be a mathematical genius to see that the second term is the reciprocal of the first term. This means that the time dimension and the space dimension behave in the same way but in opposite directions. If you are far away from the gravitational source, the distance r from r_S is large and the fraction \frac{r_S}{r} approaches zero in the time and space dimensions. This means that there is actually only a 1 in the parentheses and we have flat spacetime and no gravity. However, gravity never becomes exactly zero. This means that gravity has an infinite range. As we approach r_S,

the fraction approaches 1. At the Schwarzschild radius, it is exactly 1. In the time dimension, the parentheses become zero. The time dimension then has no more extension/length. Time stands still for a distant observer. In the radial space dimension, the parentheses also approach zero. However, it is then divided by zero and we obtain a singularity. A value of infinity, or rather undefined. This is another disadvantage of the Schwarzschild metric. With other metrics, this singularity does not occur at the event horizon. It can be shown that this is only a peculiarity of this metric, a mathematical artifact. Since the parentheses are in the denominator for the radial component, the extension/length before the Schwarzschild radius approaches infinity.

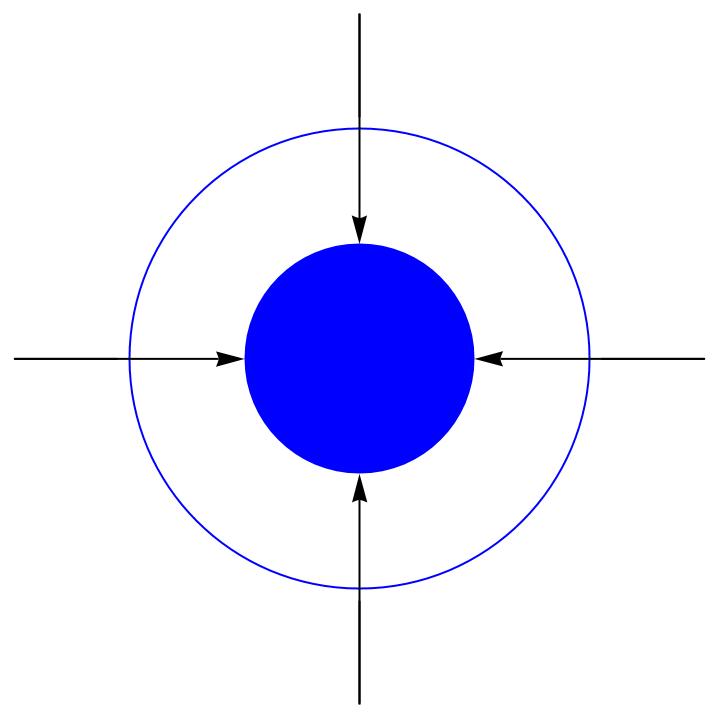

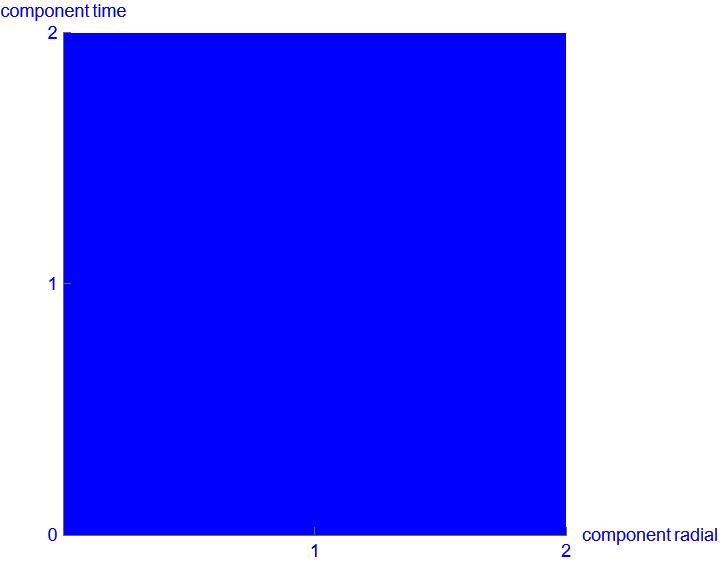

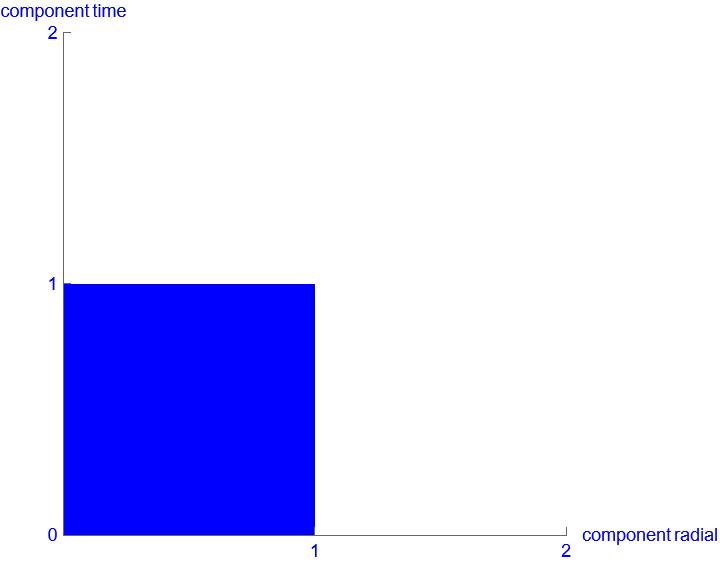

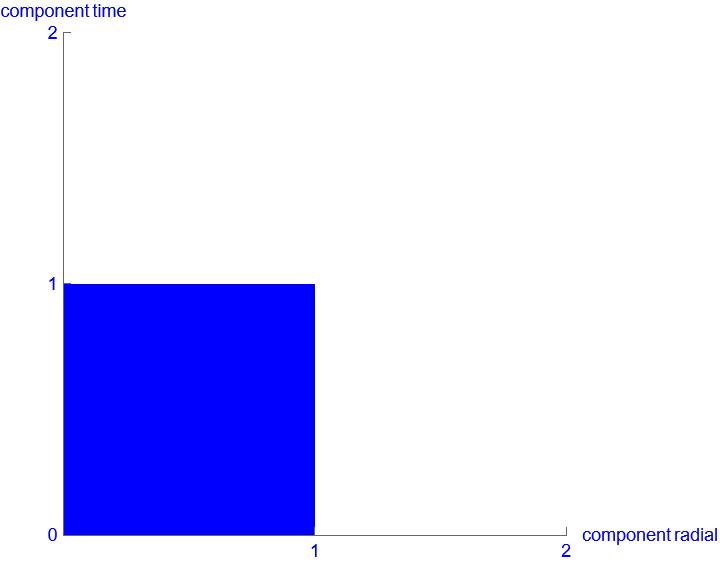

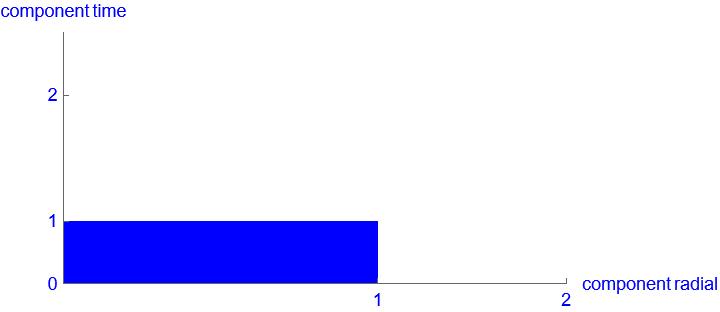

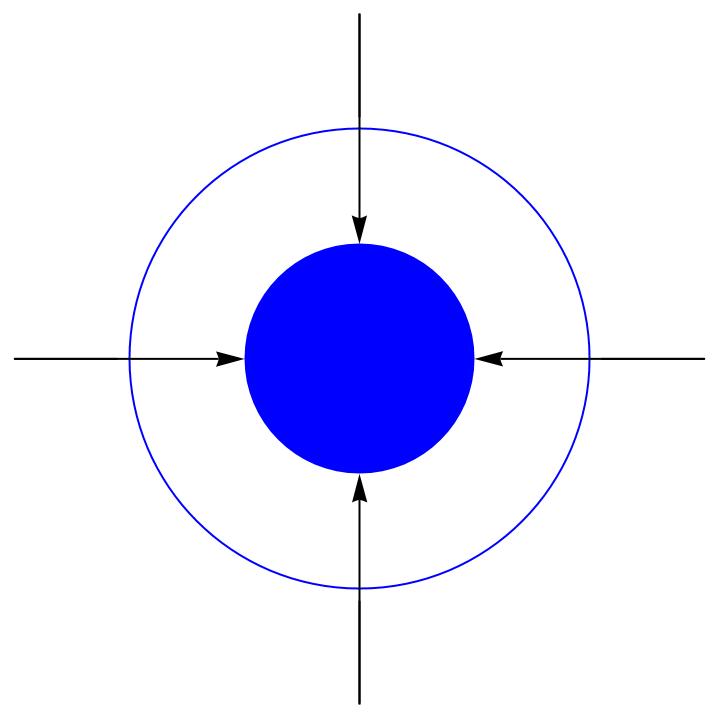

If the time and space dimensions form a rectangle, the following happens:

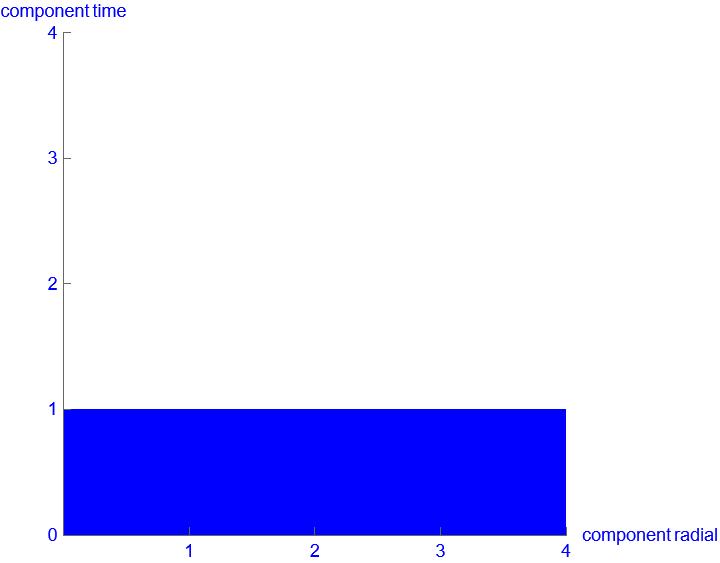

The time dimension becomes smaller and the space dimension becomes larger to the same extent. The key point here is that the area of the rectangle does not change. If the time is halved, the length doubles => identical area. This consideration of spacetime curvature is sufficient for us to justify our deformation as the source of spacetime curvature, the spacetime density.

Let’s stick with a spherically symmetric example. If the radial space component in the direction of the gravitational source becomes longer and longer, where does this additional length go? What we often hear is: into the curvature of spacetime. We want to describe the curvature of spacetime as a reaction to the density of spacetime. So, let’s turn the argument around. It’s easier if we assume that the spacetime of the gravitational source has shortened with some deformation. The spacetime curvature must compensate for this with additional length.

If you like, due to the continuity of spacetime, the curvature of spacetime fills in the missing expansion of spacetime to spacetime density.

We are looking at a spacetime volume and still have the spherical coordinates. In a space-time volume, however, it is not only a length that can become shorter due to deformation. The entire spacetime volume of the gravitational source must become smaller. We continue to assume identical behavior of spacetime during deformation. Then, in addition to the radial spatial dimension, the time dimension must also change to the same extent. Not in the opposite direction, otherwise we will not obtain a smaller volume. In this case, the time dimension must shorten to the same extent as the spatial dimension.

e deformation of spacetime for the gravitational source looks like a “density.” The previously larger area must now be accommodated on a smaller area.

Hence the name: spacetime density

How should we imagine this density? With a material such as a sponge, we can squeeze it and very easily recognize its density. Does the same happen with spacetime? Clearly not! When talking about density, we like to use the analogy of a substance. In a substance, we can recognize the density from the outside and also determine it within the substance itself. As with the sponge. The analogy of a substance is like the word density. Sometimes it fits and sometimes it doesn’t. In this case, neither substance nor density fits colloquial usage. Because nothing is being “squeezed.” In the images above, we simply shortened the lengths. That doesn’t happen. What really happened is that the definition of geometry changed.

The fact that the definition of spacetime geometry changes and nothing is stretched or squashed cannot be emphasized enough. This is a key point for a understanding of DP. We redraw the two images of spacetime density with the correct divisions on the coordinates. It then looks like this:

Can you see the difference? The step size of a unit of length remains 1 in both images. What has really changed here is how a meter is defined for a spatial dimension and a second for the time dimension. This is only within the spacetime density. This means that each rectangle has an area of 1. Locally, there is no change. Only when comparing the rectangles can one see that the definition of time and length must be different.

Spacetime density is actually a “density of the definition of the geometry of spacetime” or a “density of the spacetime definition.” These are long terms or obscure abbreviations. We’ll stick with spacetime density.

Five times in bold: “definition.” I hope that has stuck. Nothing is condensed as it would be with a substance. In the metric of spacetime, there is no classical expansion or density. The definition of what the unit of length 1 meter or the unit of time 1 second is, is changed. This shorter definition is the higher density. Only with this view of the definition can we later construct a principle of relativity and derive the important conclusion of the “limits of spacetime.”

We can also do this with the sponge.

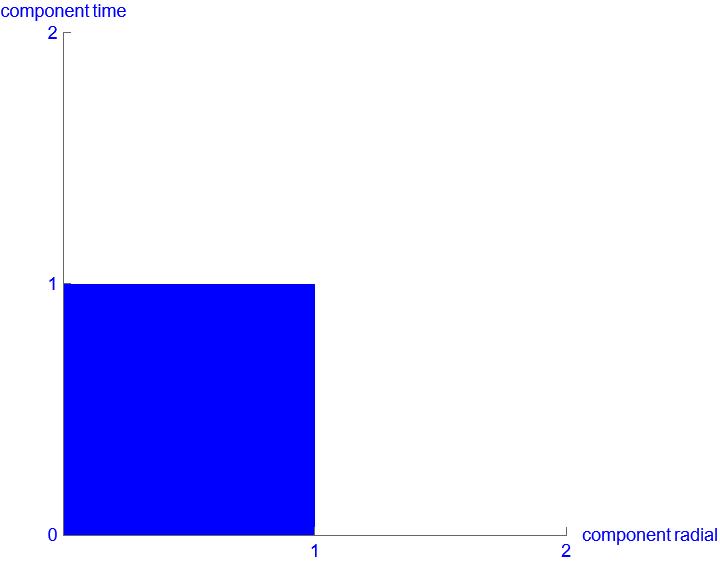

What has just been said about spacetime density also applies to spacetime curvature. Here is the spacetime curvature with the correct divisions in the drawing:

There are more names to define. In SR, the individual components have been referred to as length contraction and time dilation. We will continue to use these terms in exactly the same way. For spacetime density, time dilation is used for the time dimension and length contraction for the space dimension. In the case of spacetime curvature, the time dimension is also defined as smaller, which means that this is a time dilation. However, there is no separate term for the change in the spatial dimension in spacetime curvature. In this case, the term spacetime curvature is often used directly. From now on, we will only use spacetime density and spacetime curvature to describe the behavior of the entire spacetime. In order to remain consistent with the same syntax, we will use the term length relaxation for the change in the spatial dimension in spacetime curvature.

Every individual, every planet, and even every single elementary particle is a spacetime density in a single object, spacetime. This is continuous. There are no boundaries within spacetime. According to DP, we are all together and physically speaking, completely correct, just different spacetime densities in a single spacetime. This approach thus represents the strongest collective thought we can apply.

QM will have a slightly different opinion on this. However, for GR, this is 100% true. We should always keep this collective thought in mind when dealing with other individuals. According to DP, this is always a way of dealing with ourselves. The thought is as beautiful as it is frightening.

At the end of this chapter, we want to test our assumption of spacetime density at a high level. We only need to be able to explain the behavior of GR based on geometry. The mathematics, the how, will not be changed. Our goal is to be able to explain the why to mathematics. The assumptions that led to SR and GR, the principle of relativity, the speed of light, and the equivalence principle are discussed in separate chapters. This will be the actual test. We must be able to generate these assumptions from our approach. We cannot reuse them, otherwise we will end up with a circular argument. The starting point was already GR. Let’s go through a few points.

For us, spacetime curvature is the reaction of spacetime to spacetime density. Since spacetime density “contracts,” spacetime as a continuum must compensate for this. The curvature of spacetime must necessarily align itself in the direction of the spacetime density. In the first approach, the spacetime density has no direction. A density can be described as evenly distributed over the volume. This makes the curvature of spacetime a vector quantity and the spacetime density a scalar quantity. In the next chapter, we will derive that a spacetime density can be scalar and vectorial.

We can rearrange the formula of the field equations. We bring the Einstein tensor to the same side as the stress-energy tensor. This rearrangement is allowed for any equation.

0\space =\space k\space *\space T_{\mu\nu}\space -\space G_{\mu\nu}

Now the spacetime density and the spacetime curvature must cancel each other out. A sign change for a geometric mapping is always a change of direction. This means that the space curvature now pulls away from the spacetime density. The spacetime density is now “pulled apart” by the spacetime curvature. This is no change for spacetime, i.e., it is equal to zero.

Let’s take another look at Figure 2-3. Memorize the image well, as we will need it again later.

We see that the spacetime curvature deforms spacetime toward spacetime density. This means that the spacetime outside the ring must be deformed toward spacetime density. Spacetime is a continuum and must not “tear”.

If something deforms in one direction, then the neighboring area must also deform in that direction. Then the neighboring area of the neighboring area must deform, and so on. Therefore, the spacetime curvature must have infinite range.

The effect of gravity decreases with distance. This decrease must be greater than linear. With distance away from a spacetime density, spacetime curvature can access an ever-increasing spacetime volume that must deform. Therefore, the attenuation in our 3D spacetime must occur with the square of the distance. In the opposite direction of gravity (away from the spacetime density), a one-dimensional space dimension is added to the volume by two spatial dimensions. If we consider the blue ring as a spherical shell in 3D, we can place ever larger spherical shells around the spacetime density. The distance r of the spherical surface on which gravity acts grow linearly. However, the surface itself grows with r^2. The spacetime curvature can use the distance from point to point to compensate for an ever-increasing surface area. This means that this growing surface area has to counteract this less and less, and the spacetime curvature decreases with r^2.

Let’s stay with Figure 2-3. We can see that space-time must “follow” the spacetime density with the spacetime curvature. Spacetime must compensate here. Then it only makes sense for spacetime if the pushing is done by the spacetime curvature in such a way that the spacetime density of the surrounding spacetime does not change due to the spacetime curvature up to the gravitational source. The spacetime curvature must therefore be a deformation of spacetime that does not itself cause any change in spacetime density. Even “empty” spacetime without a particle is spacetime and therefore has a spacetime density. Based on the approach with spacetime density, the spacetime curvature must exhibit the known behavior. The area of spacetime does not change, and the spacetime density at the spacetime curvature therefore does not change either.

Let’s stay with Figure 2-3. We can see that spacetime must “follow” the spacetime density with the spacetime curvature. Spacetime must compensate here. Correct! The beginning repeats itself. This is not a mistake. We need these statements again here.

The spacetime curvature must compensate for the gap between the ring and the disk. However, this also means that the spacetime curvature must explicitly not compensate for the spacetime density. For the spacetime curvature, the end is reached at the boundary of the spacetime density. There is already too much spacetime in the spacetime density. The spacetime curvature must not extend into it and exacerbate the problem.

Important! Spacetime curvature is not there to set spacetime density to zero. Due to the continuity of spacetime, it must compensate for the missing length up to spacetime density. Spacetime curvature should not dissolve spacetime density. Only the amount of spacetime density is relevant for spacetime curvature, since a larger spacetime density must compensate for a larger gap. Whether spacetime density has an “internal” structure is completely irrelevant for spacetime curvature and thus for GR. QM will then describe precisely this “internal” structure.

Spacetime curvature is a compensation for a “spacetime gap” caused by spacetime density. Spacetime density itself is not changed by spacetime curvature. Spacetime curvature ends at the boundary of spacetime density. Here we can already see how we will later get rid of the singularity in GR. Spacetime density without spacetime volume makes little sense. No volume, no density, no gravity, and therefore no singularity due to gravity. We will discuss the mathematical abstraction of a point and thus the singularity in detail in Chapter 3, “Limits of Spacetime.”

Let’s stay with Figure 2-3. We can see that spacetime must “follow” the spacetime density with the spacetime curvature. Spacetime must compensate here. Yes, again!

What we can also see is that spacetime has condensed into a disc due to higher spacetime density. The spacetime density in the disc is irrelevant to GR. The amount of spacetime density determines the size of the disk, and this is what interests spacetime curvature. Thus, the spacetime density in the disk can be assumed to be evenly distributed. The description of spacetime density can therefore be done in a linear description. This will be one of the reasons why QM can be described linearly.

This is not the case with GR. Spacetime curvature does not change the spacetime density itself. However, as we can see, spacetime curvature “pushes” additional spacetime toward the spacetime density. This means that the spacetime density has increased slightly again due to the circular spacetime curvature. This results in a self-reinforcing effect. The mathematical description of GR must not be linear under any circumstances.

The wish of all physicists is that, when GR is unified with QM, GR can possibly also be described linearly from a QM approach. Linear descriptions are easier to solve. In QM, however, the description is extremely complicated from the ground up. It is only because this is a linear description that anything can be calculated at all. The description of GR is not as complicated and is very well understood mathematically. Unfortunately, however, GR is not linear. This means that supercomputers are busy calculating approximate solutions in both areas.

Finally, we will select a topic that does not belong to GR. We want to see that the approach with spacetime density also applies in other areas of physics. To do this, we will select something that exists in many different forms. We want to cover a broad spectrum. In addition, we choose something that no one sees as problematic. The perspective in physics is set to change fundamentally. This also includes areas that are supposedly considered “understood.” The choice fell on binding energy.

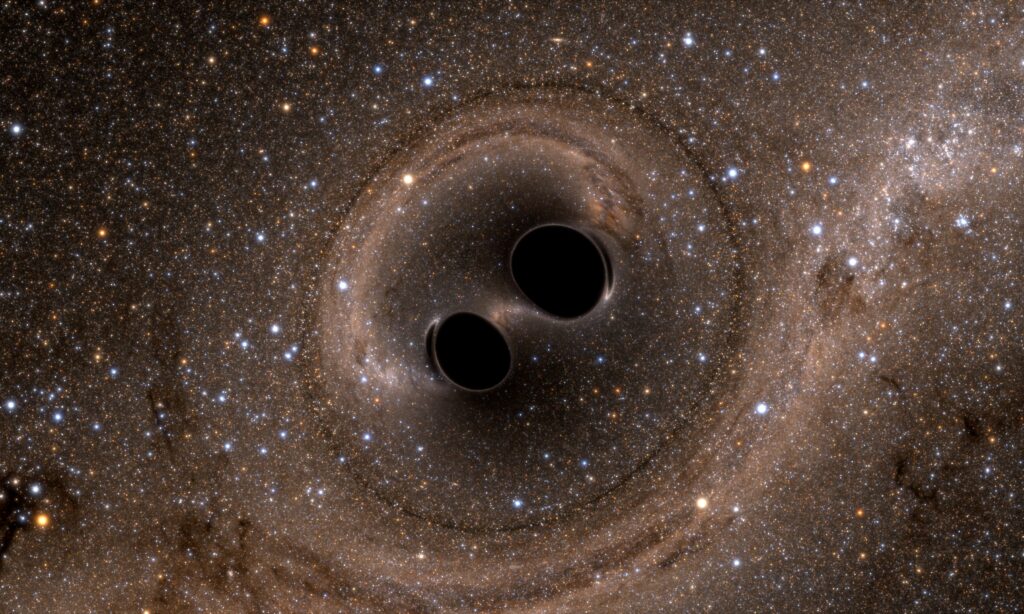

Binding energy exists in the atomic nucleus, the atomic shell, between atoms or molecules. Even the release of energy during the merger of two black holes can be explained according to this model. The overall structure has less energy than the individual parts before binding. Let’s take the fusion of hydrogen into helium as an example. There are several processes in the sun that convert hydrogen into helium. We will simplify the process greatly. This is sufficient for our purposes.

We assume that hydrogen H_1 is converted into hydrogen H_3, which then fuses into helium H_4 We are only interested in the result, the helium nucleus.

QM calculates exactly the probability of this fusion occurring and the energy that must be released in the process. The form in which the energy is released is not relevant here. We start our question game: Why? Then you often get two answers.

Unfortunately, these are not answers to the question. Why stable energy levels, entropy? The question game can be played for a long time here. What is important for us:

Mathematics is a consistent description of nature for physics, through a suitable model. With this model, we can conduct investigations and make assumptions. However, mathematics will never create or enforce anything in real nature! The “why” must clarify this question, and the model description can then add a suitable “how.”

Let’s explain this using spacetime density. The two H_3 building blocks must be spatially close to each other in order to form a bond. Bonding only works when they are spatially close. In this case, the two building blocks must come so close together that the strong nuclear force can have an effect. We will clarify the exact process of which nucleons are allowed to react with each other later in QM.

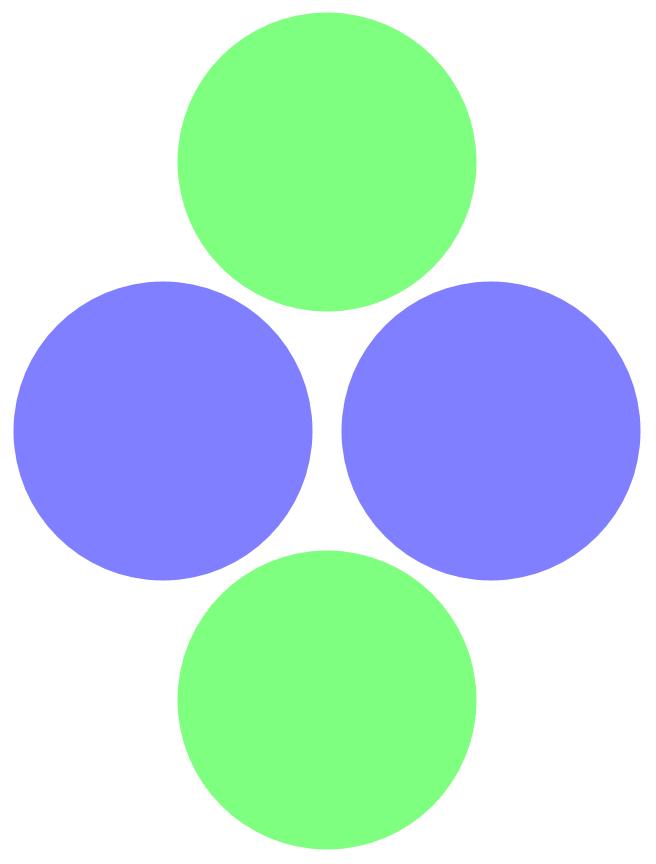

The point here is that, in the result, 2 protons and 2 neutrons form a helium nucleus. Textbooks often use a sphere per nucleon to illustrate this. We will try to do the same here. We will ignore the fact that a proton or a neutron are themselves composite systems.

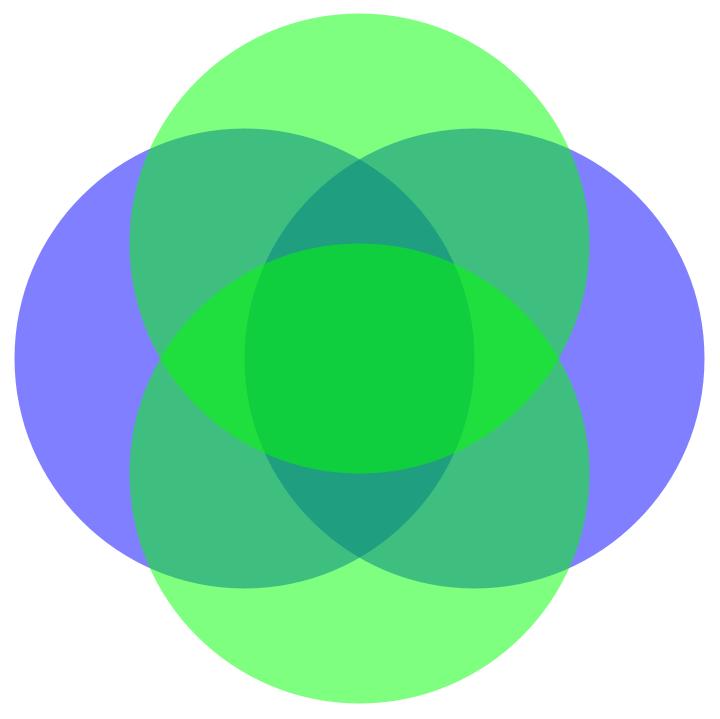

We now know that the helium nucleus does not look like this at all. Experiments have shown that an atomic nucleus must look more like a single sphere with bulges. Calculations based on quantum mechanics confirm this. How do we get from 4 individual nucleons to a sphere that is not much larger than the individual nucleons? Fortunately, we have our spacetime density.

A spacetime density is not a structure with a closed boundary. Everything is spacetime. This means that individual spacetime densities can overlap. Therefore, bonds only work from a certain spatial proximity. To us, the helium nucleus looks more like this.

The individual nucleons are a spacetime density. A spacetime density can overlap. With the overlap, each individual nucleon has too much spacetime density to be a proton or neutron. In order for the nucleons to remain at their level of spacetime density, part of the spacetime density must be removed. There is too much of it! The nucleons do not want to drop to a lower energy level. The nucleons must remain at their specified energy level. If we want to break this nucleus down into its components, we must restore the missing spacetime density. The spacetime density approach thus explains binding energy very simply. Here is a brief overview of binding energy.

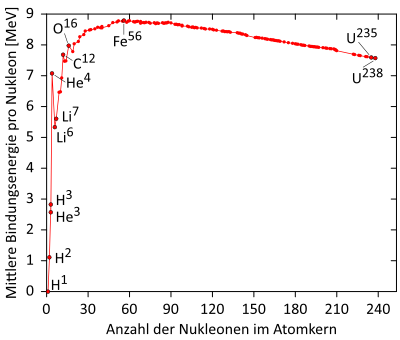

As we can see, the binding energy increases very sharply with few nucleons. This makes sense, since at the beginning, each individual nucleon creates a new large intersection of spacetime density. The more nucleons already present in the atomic nucleus, the smaller the new intersection between the spacetime densities.

At a certain number of nucleons, the binding energy can decrease again. The repulsion caused by the charge ensures that the nucleons cannot overlap arbitrarily. Therefore, the geometry of the overlap can also result in less binding energy when a new nucleon is added. In iron Fe_{56}, this is the end. Each new nucleon causes a smaller intersection due to the change in the intersections between the spacetime densities.

In addition, there are so-called “magic numbers” 2, 8, 20, 28, 50, and 82. This number of nucleons appears to have a very stable bond. According to QM, when the atomic nucleus is “deformed,” these numbers result in an almost exact sphere for the entire atomic nucleus. A smooth sphere as a whole has the highest possible intersection of nucleons.

As we can see, we can use the concept of spacetime density to explain the “why” even in areas outside of GR. This concludes this chapter. In the next chapter, we will look at the most important conclusion drawn from spacetime density: spacetime has boundaries. In this new chapter, spacetime density will be further defined using the idea of spacetime boundaries. But we are not done yet.